It happened almost 35 years ago. The elders in my village had assembled to discuss a curious demand by the samiyadi (oracle) of the local Sudalaimadan temple, the presiding deity of graveyards. He insisted that the village should organise a kodai (festival) as the deity was very particular about it.

“He is not letting me sleep. If you organise the kodai, I will continue to perform the puja,” he said, and placed the keys of the sprawling graveyard, with its banyan and neem trees, before the elders.

Sudalaimadan

There was an air of scepticism. Those familiar with the Vaishnavite tradition, however, accept such interactions between a god and his devotees. Legend has it that Thirukachi Nambi, one of the gurus of philosopher Ramanuja and founder of Vishishtadvaita, used to converse with Varadharaja Perumal, the presiding deity of Kancheepuram.

Offerings of elongated ears

Guardian deities are colourful characters and they share a strong bond with their devotees. In Tamil Nadu, there are folk deities with pan-regional appeal, those worshipped in a specific area, and deities of particular communities and families.

Ballads narrate their stories. They are fearsome, ferocious, and capable of punishing wrongdoers. They drink liquor, smoke cigars, and eat meat. During kodai, goats, roosters and pigs are sacrificed to propitiate them. (In the southern part of the State, padiappu is an important offering to folk deities. Sacrificed animals are cooked and offered with rice, vegetable curry, a stir-fry of drumstick leaves, pappad, boiled eggs and lashings of ghee.)

In Srirangam, a neighbourhood of Tiruchirappalli, Muniappan is the guardian deity of the first Vaishnavite temple (among the 108 in the area). He occupies the entrance of the rajagopuram (entrance tower). Just outside the shrine is a small bowl on a makeshift stand where devotees drop surruttu (cigar) as an offering — praying that their problems would vanish like smoke. While in Tiruvarur, a town on the banks of the Cauvery, and a holy place for Saivaites as it houses the biggest temple of Lord Shiva, the Aazhi Ther (chariot festival) begins only after a kodai for Pidari, a folk goddess.

Offerings of surruttu to Muniappan

| Photo Credit:

Moorthy G.

I’ve always been fascinated by folk deities, and my childhood passion was strengthened by watching folk art forms such as Naiyandi Melam, Kaniyaan Koothu, Villupaatu and Thappu.

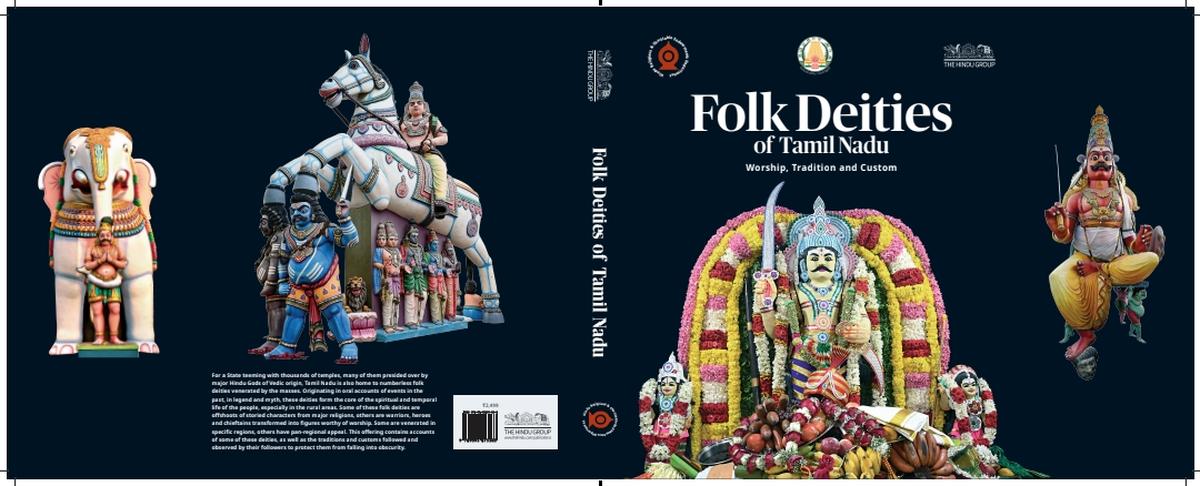

Recently, I got to revisit it while curating Folk Deities of Tamil Nadu. While putting together the coffee table book, I travelled across the State for two months, and visited over 60 villages in search of local legends, and the myriad customs, traditions and ways of worship associated with them.

Folk Deities of Tamil Nadu

People’s faith, I discovered, is still strong. At S. Kovilpatti, a village in Sivaganga district, men carve out a portion of their earlobe even today — as atonement for the wound one of their ancestors accidentally caused Ayyanar, a deity of prosperity who is worshipped by farmers of the wetland and rain-fed areas. They also follow the custom of elongating their earlobes by wearing weighty rings right from their childhood.

Devotees elongate their earlobes right from their childhood

In Valangaiman near Thanjavur, devotees observe a morbid ritual. On the day of Padaikatti (coffin festival) of the local Mariamman temple, the entire village resembles a graveyard.

Scores of devotees — kumkum on their foreheads and bodies covered in holy ash — are carried on biers. Their toes are tied with rope, their eyes covered with sandal paste, and a coin fixed on their foreheads, as if they were dead. The ritual is performed to fulfil their vow to the deity, for giving them ‘a rebirth’ after a serious illness.

At the Padaikatti festival at a Maha Mariamman Kovil in Valangaiman

| Photo Credit:

M. Moorthy

Threat of Sanskritisation

Tamil society worshipped heroes who laid down their lives for the common cause. Folk Deities of Tamil Nadu covers a few, such as Madurai Veeran, Kathavarayan, and Muthupattan, who were raised to the status of guardian deities after being killed for questioning the norms of society. Madurai Veeran, the son of a cobbler, was killed for marrying Vellaiammal, a dancer. Muthupattan, whose temple is situated near Karaiyar Dam in Tirunelveli district, was a Brahmin who became a cobbler in pursuit of his love for the two daughters of a cobbler. He was killed on the night of his wedding by thieves. Devotees offer chappals to the deity, to honour his livelihood.

Chappals for Muthupattan

Many deities, however, are losing their original characters, and their unique forms of worship are disappearing — not just because of the passage of time but also Sanskritisation. Old temples are being demolished and concrete structures with sanctum sanctorums, vimanas and gopurams are coming up in their stead, though these aspects have no meaning in folk religion.

It is not a recent phenomenon. Long ago, ballads narrating the stories of folk deities were altered with the objective of making them an aspect of Vedic deities. “The avatar concept has furthered the Sanskritisation process. Male deities of various tribal societies were turned into Vaishnavite gods, and female deities linked with Parvathi and Lakshmi by invoking the swaroopa concept,” says Aru. Ramanathan, former head of department of Folk Studies at Tamil University in Thanjavur.

In Folk Deities of Tamil Nadu, he has addressed how Theepaintha Amman at Sethiathope in Cuddalore district was elevated as an aspect of Sita. “These changes are continuously taking place, to this day.”

Folk Deities of Tamil Nadu is jointly published by The Hindu Group and the Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments Department.