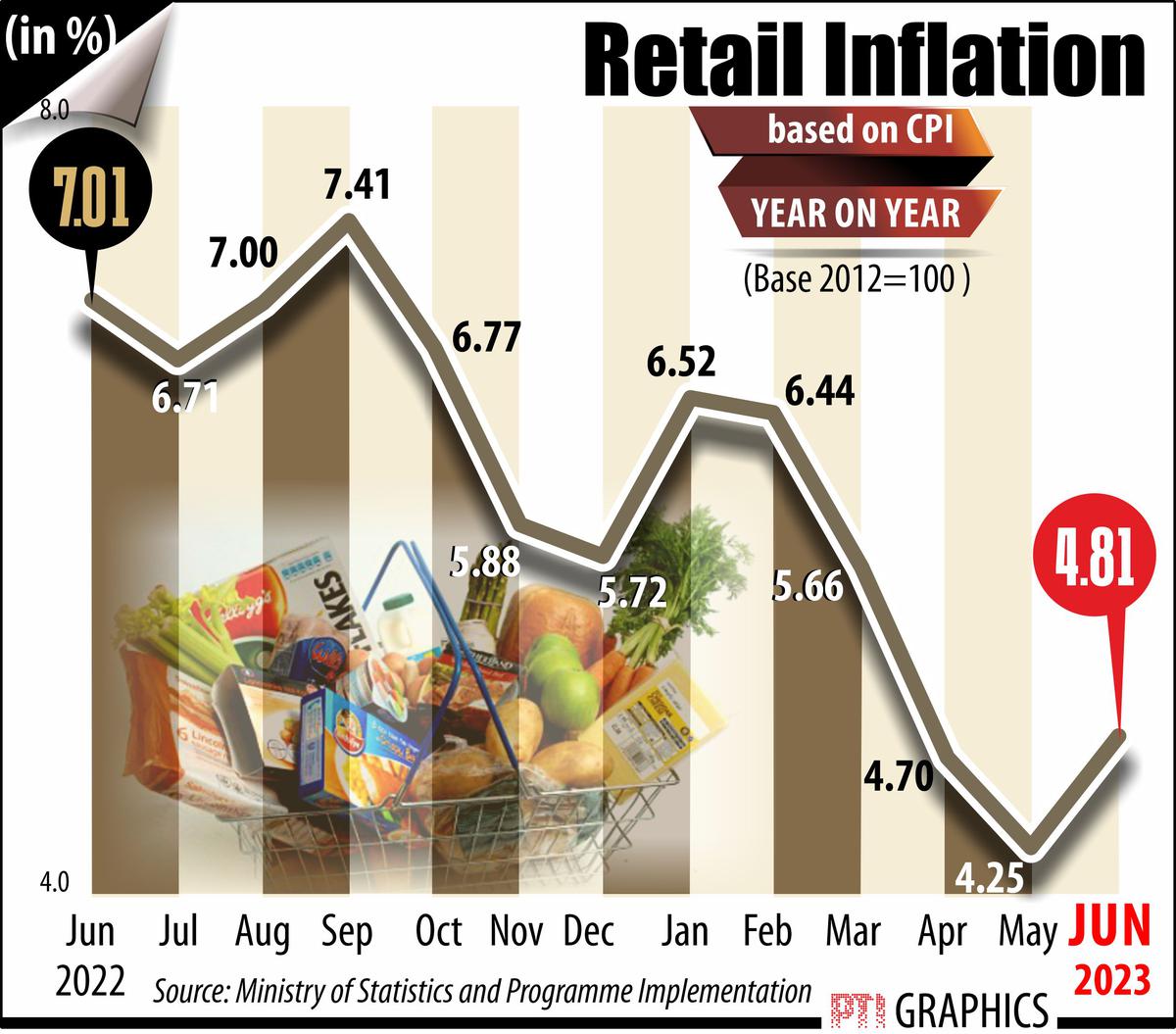

A laborer carrying vegetables at Azadpur Mandi in New Delhi on July 12, 2023. Photo credit: PTI

IThe magician is entering an antique shop and comes across an old wooden trunk. You notice a dusty corner where an old radio sits beside a pile of audio cassettes. Suddenly, you are transported to a time when these items were cutting edge technology, a time when their presence in homes was commonplace. However, today, these items are considered obsolete. This nostalgic view may be a metaphor for our current process of tracking the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and then calculating inflation. We continue to monitor a basket of goods that includes flashlights, radios, tape recorders, CDs, DVDs, audio/video cassettes and trunks, among approximately 300 other items. Although these are of minimal importance in the overall CPI calculation, we cling to the past, tracking down items that no longer hold the same relevance in our consumption patterns.

a grow basket

The CPI basket should not be viewed as an unchanging artifact frozen in time. In contrast, the actual consumption basket of a common Indian is fluid and constantly evolving, reflecting changes in social needs, priorities and economic conditions. As time progresses, the consumption patterns of individuals and households inevitably change. Technological progress introduces new products and services.

It is not just these things that make the CPI flawed. In the current CPI (base year 2012), the weighting of the different groups are as follows: food and beverages (45.86); paan, tobacco and intoxicants (2.38); clothing and footwear (6.53); housing (10.07); fuel and light (6.84); Miscellaneous (28.32). The weight of food in the CPI basket has declined from 60.9 (in 1960) to 57.0 (in 1982) and 46.2 (in 2001). This gradual decline shows that as the economy grows, the proportion of income spent on food declines. This general trend is known as Engel’s law, which states that as income increases, the proportion of income spent on food decreases, even if absolute expenditure on food increases. The high reliance on food inflation today sets Indian inflation apart from many other developed countries where the weight of food is much lower.

These changes mean that as people’s incomes increase, they allocate a greater proportion of their spending to non-food items such as housing, education, health care, personal care, entertainment and digital services such as the Internet. This reflects a general improvement in living standards and expansion of consumer demands.

Moreover, the shockingly high weighting of 9.67 given to cereals in the current CPI is undoubtedly excessive and highlights two important issues. First, as nations undergo economic advancement and social progress, a typical trajectory involves diversifying food intake and adopting a wider range of nutrient-rich alternatives beyond cereals. This paradigm shift in dietary habits would undoubtedly have manifested itself in the last decade, which would have reduced the relative expenditure on cereals. Second, the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana has substantially reduced the cost of food grains for a large section of the population. This has probably resulted in a change in consumption patterns and a further reduction in relative expenditure on cereals.

There are other examples too. Ashok Gulati writes about how tomatoes, onions and potatoes have a significant impact on inflation. It should be less. The current rising tomato prices will have a disproportionate impact on the CPI.

consumption expenditure

Although it is essential to understand the evolution of consumption patterns with increasing economic prosperity, the challenge lies in effectively reflecting these changes in our inflation metrics without access to the latest consumption expenditure data. The weighting for the CPI may undergo a significant change only after the data from the Household Consumption Expenditure Survey (CES) data is received. Currently, the Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation (MoSPI) is in the middle of CES, with the first round ending in July 2023 and the second round a year later in July 2024. The ministry will need an additional three to six months to process the collected electronic data. However, one must be bothered by such long processing times in this digital age. Even so, when the CES results are finally published around December 2024, it will still take several more months to build a new CPI based on this fresh data.

So, we find ourselves in a dilemma: We’ll be relying on older parameters like DVD players and trunks to measure our inflation for at least the next two years. This is not merely an ideological challenge; It is a question of how accurately we are measuring the cost of living and economic well-being. In a rapidly evolving digital economy, our data collection and inflation estimation methods must simultaneously adapt and evolve to ensure they accurately reflect the realities of modern consumption and life.

The absence of CES has given rise to several issues. We are unable to accurately determine the population below the poverty line, and our ability to effectively track inflation is severely weakened. Our tools to understand and manage our economic reality are grossly inadequate. Consequently, it is of utmost importance for MoSPI to address these deficiencies immediately. Additionally, efficient data processing should be a non-negotiable priority. Finally, for MoSPI to sit indefinitely on the findings of various surveys is an abdication of responsibility that India cannot afford.

Bibek Debroy is the chairman of the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister; Aditya Sinha is Additional Private Secretary (Policy and Research) in the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister