Ammani Ammal was part of a devadasi troupe that went on an 18-month tour of France

Somewhere in Paris, a winding stone walkway lined with Haussmannian buildings leads to a small iron gate. Beyond the tree-lined path is a house, now converted into a museum, housing within its main chamber, a glass cabinet. A bronze statue of Ammani Ammal, a devadasi, is seated, staring at the world around her through a glass pane. How did Ammani end up in Paris?

In the year 1838, a group of temple dancers and musicians associated with the Vaishnava temple in Thiruvananthapuram was approached by the French impresario EC Tardival for a series of concerts in France. Originally from Pondicherry, this talented troupe was offered ten rupees per day, plus five hundred rupees in advance, and an additional 500 on the completion of their 18-month tour. After mutual consent, much effort was put into drafting a contract to exempt these artists from temple service and to be signed entirely in French at a French notary. All the details of his stay and program were recorded. Of the eight-member troupe, seven signed their names in Telugu and one in Tamil – providing an interesting glimpse into the community’s cultural cosmopolitanism.

Tardival arranged a boat trip to Bordeaux, where they all arrived on July 24, 1838, to see a ballet. Historical accounts describe her presence in the audience as a spectacle in itself, quite a distraction from the Western classical dancers on stage. He eventually made his way to Paris, and after being greeted by King Louis Philippe, he was placed in a bungalow with guards on the banks of the River Seine. From here, they would eventually visit London, Brighton and several other European countries.

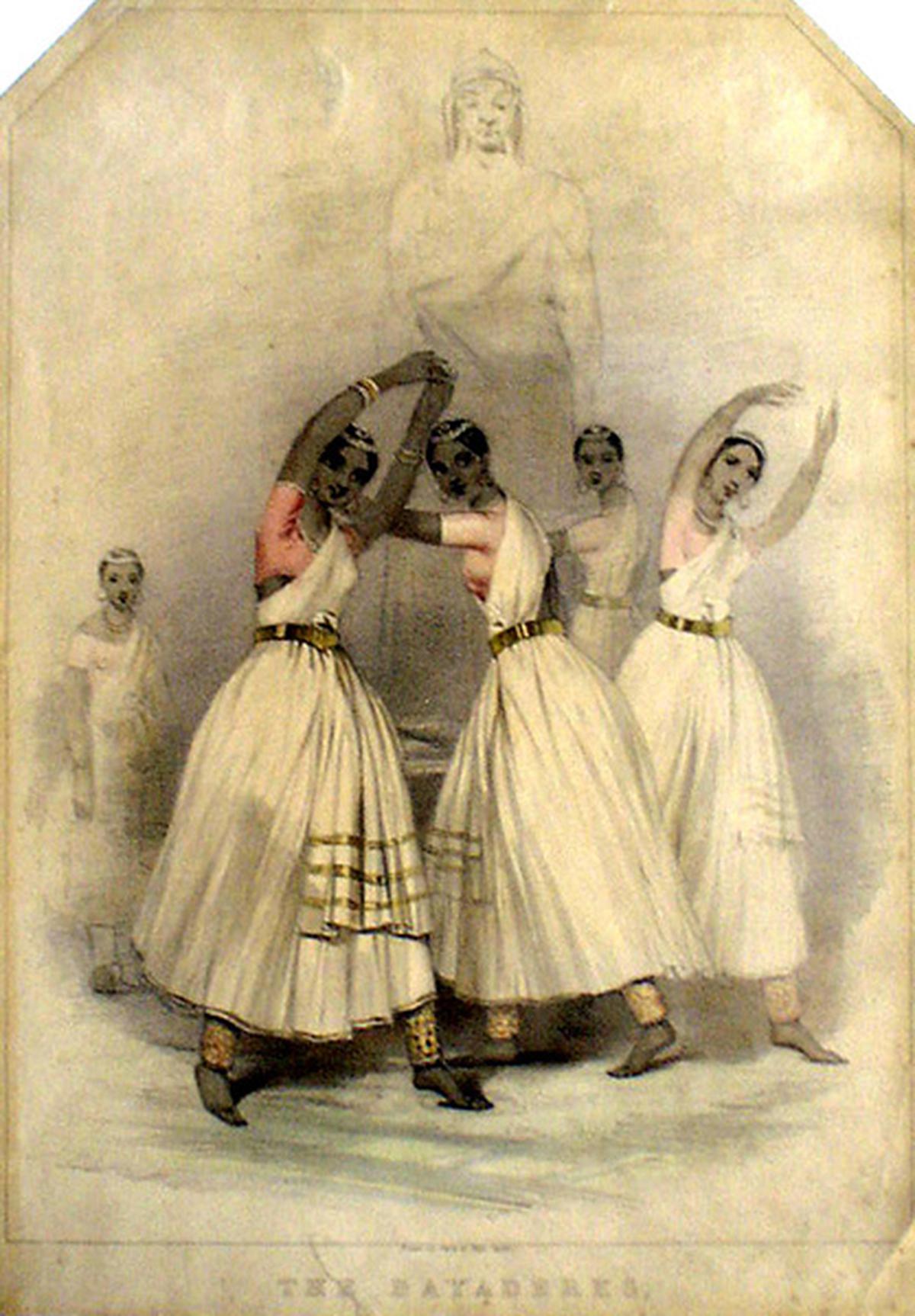

A lithograph showing the group dancing ‘Malapo’. photo credit: New York Public Library

The troupe consisted of five female dancers, including six-year-old Vedam (described by the French as “Cupid painted black”) and Thillai, who was in his 30s. Thillai danced with his two daughters, Soundiram and Rangam, both aged 14, and his 18-year-old niece Ammani, the lead dancer. He was accompanied by three male musicians playing Nattuvangam, Madalam drums and Thoothi bagpipe-horn for the pitch. Ammani was, by all accounts, tall, slim and stunning. His charisma was such that his departure from Pondicherry provoked a boy, whom he called, to jump into the water and swim towards his departure ship.

The repertoire of these artists may be unrecognizable to a modern Bharatanatyam dancer. With names translated by foreign organisers, such as ‘The Robbing of Shiva’, ‘The Dagger Dance’ and ‘The Widow’s Lament’, it is difficult to understand what exactly they danced. Two particular pieces stand out for their resemblance to the modern Bharatanatyam repertoire – the first was titled ‘Salute to the Rajah’ by Vedam. It was probably a variant of the salam-daruvu or shabdam, traditionally used to greet the king. The second piece (and possibly the most commonly written) was Malapau which bears some resemblance to Alarippu and features three dancers simultaneously on stage.

As influential as they were, no one stood as prominently as Ammani. Everyone who saw him and his dance was speechless, especially Jules Théophile Gaultier, a playwright, poet and critic. He was incognito for private rehearsals at the dancers’ bungalow in Paris. His writings reflect his love for his physical and theatrical presence. “Olive-gold skin, silky rice paper texture to the touch, rounded hips” he observes, paying attention to detail to her jewelry. He went to the extent of commissioning the popular sculptor Jean-Auguste Barre (who had worked on the sculptures of many prominent ballerinas) to cast the image of Ammani in bronze. This two-foot-high piece of art sits in Paris, chilling Ammani (spelled as Amani by Barre) in a pose from the famous Malapau.

A lithograph shows dancers striking a pose while performing ‘Malapo’. photo credit: British Library

At first, the monochrome Ammani feels generic compared to some of the stunning bronzes that pop out of the Indian Sears-Purdue repertoire. Yet upon closer examination, Barre’s attention to detail is striking – Ammani’s sari is filled with zari checks and each of her jewellery. Her salangai, odiyanam and mukuthi are executed with great detail, as is the long flowing braid that slides down her spine. The hallmark of this sculpture is the way Jean Auguste Barre captures the movement. Ammani leans completely to one side, but still has control over her spine – a feature that is often lost in our modern practice. Her unusually thin waist was probably an exaggeration to suit the European aesthetic of the female body. Ammani still stands in the middle of a dance in a small Paris museum, waiting for us to find her.

The writer from Bangalore is a dancer and research scholar.