text size:

aThere have been reports of the Narendra Modi government agreeing to all the demands of the protesting farmers, including Guarantee for MSPIndia should question the possible support pricing regime and its direct financial implications.

Questions of equity and sustainability are yet to be considered – which class(s) of farmers have surplus to sell? Which areas have better infrastructure for procurement? What will happen to the rainfed farmers who do not get input subsidy and do not have access to the procurement system? These can be addressed later.

But first, we need to bring conceptual clarity on demand. Is there a demand for ‘compulsory’ MSP or a legally guaranteed MSP? There is a difference.

A mandatory MSP means that it would be illegal to buy any notified commodity anywhere in India at less than the MSP. If MSP is made mandatory, the government (reed inspectors) will have to ensure that every single transaction confirms this legal requirement. Any violation will have to be punished. It may be safer for traders to stay away from the market and wait for the government to unload the stock. The government then becomes the sole trader? A sure recipe for disaster.

The current demand appears to be for a ‘legal’ guarantee (faith-based system versus rights-based one) that the government (state and union) will buy all the goods offered at the MSP. It will be like an expanded pan-India procurement operation similar to Punjab and some other states. Farmers have been demanding (obviously lacking trust and therefore a rights-based system) that the scheme be included in legislation like the National Food Security Act (NFSA), which ensures the ‘right to food’. Cash payment against food grains is also provided as ‘fall back’ provision under NFSA. Therefore, a ‘guaranteed’ MSP can be a purchase plan, a price reduction payment option, or a combination of both. If this is the way forward, what will be the consequences?

Read also: What did the peasant movement achieve? Original movement Gandhi, Gandhi has an answer

cost implication

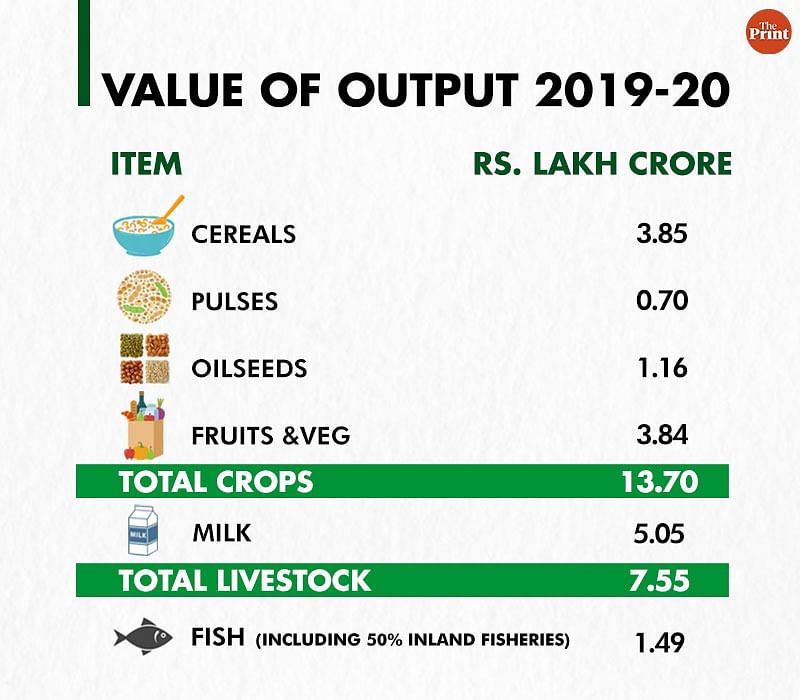

Is the demand for legal guarantee limited to 23 items already covered under MSP? If so, what are the reasons for excluding farmers growing crops outside the MSP regime? There is no certainty that non-MSP farmers will not demand MSP. To understand the potential impacts, let us take a look at the value of production in agriculture.

Presently the value of 23 crops under MSP is approx. Rs 7 lakh crore, Leaving aside administrative and logistics considerations, let us look at the cost impact of such a proposal.

Kiran Visa and Yogendra Yadav has argued that if a legally guaranteed MSP is provided, it will only cost the government an additional Rs 47,764 crore (2017-18 data). This calculation does not take into account, among other things, the current total food subsidy of about Rs 240,000 crore, which is mostly consumer subsidies.

If the proposal for legal guarantees is taken forward, the government will have to continue with the current procurement policy, add price shortfall payment guarantees and manage a hybrid system. In such a scenario, the government would continue with a food subsidy of Rs 240,000 crore (since the MSP goes up every year and prices remain constant) and would add over Rs 50,000 crore every year. Since a lot will depend on market conditions, the government will have to look at bills of Rs 300,000 crore or more on this account.

hindrances

Cereals (other than wheat and rice), pulses and edible oils are purchased, and sold at select auctions under an elaborate “open market sale scheme”, mostly at low prices. If we go by the history of sale of wheat and rice in the open market, the net loss to the government would be more or less equal to about 40-45 per cent of FCI’s MSP. Therefore, given the low distribution cost, the subsidy burden of any procurement operation will not be less than 30 per cent of the value. It is risky to estimate the cost of even a legally guaranteed MSP for 22 crops (except sugarcane). Market prices and quantities can vary greatly. But looking at the example of wheat-rice, the government may have to consider the following:

- MSP, backed by some sort of government guarantee, can be substituted with ‘limited’ physical purchase and payment of shortfall in price. An open-ended purchase involving PDS and open market sale of surplus would be disproportionately expensive and difficult to implement. Is it time to decouple MSP from PDS purchase?

- The government needs good reasons to convince and convince farmers growing non-MSP crops why MSP is being limited to 23 crops. They may choose to change the MSP crops to ‘tomato, onion, potato’, creating yet another set of issues on top.

- Given the estimated revenue receipt of the central government at Rs 88 lakh crore (21-22 BE), can the government increase the food subsidy from Rs 2,40,000 crore to over Rs 300,000 crore? This is in addition to PM Kisan, fertilizers and other subsidies.

- Whether the government can reduce its coverage under the NFSA, given the latest multi-dimensional poverty data, makes the case for reducing coverage to 40 per cent stronger and for PDS to partially offset the subsidy burden. Does the issue revise the prices under?

- Do the ideas of equity and sustainability demand that the government shift to a PM Kisan type of income support system to take care of fruit and vegetable, dairy and rainfed sector farmers considering their production and price risks?

- Shouldn’t state governments be actively involved, given more flexibility and take primary responsibility for improving farmers’ income?

Legal guarantee for MSP is not an easy issue. This requires extensive consultation. A hasty resolution is likely to lead to chaos and long-term damage.

T Nand Kumar is former Union Secretary, Food and Agriculture. Thoughts are personal.

(Edited by Anurag Choubey)

subscribe our channel youtube And Wire

Why is the news media in crisis and how can you fix it?

India needs independent, unbiased, non-hyphenated and questionable journalism even more as it is facing many crises.

But the news media itself is in trouble. There have been brutal layoffs and pay-cuts. The best of journalism is shrinking, crude prime-time spectacle.

ThePrint has the best young journalists, columnists and editors to work for it. Smart and thinking people like you will have to pay a price to maintain this quality of journalism. Whether you live in India or abroad, you can Here,