Form of words:

NSDue to a rapid global economic recovery, Indian exports are on the jump. Country recorded Its highest ever FDI in FY2020/21 is $81.72 billion. foreign exchange reserves Huh at an all-time high of $620.57 billion. Most forecasts say that India’s GDP will be to grow double-digit rate in the first quarter of the current financial year. The cut in corporate taxes coupled with lower interest rates and ample liquidity has resulted in better profitability, and in turn, has ensured that bulls dominate India’s stock markets.

Despite this apparent enthusiasm, India’s economic recovery has remained one-sided, firing on two, or more precisely, one-and-a-half cylinders – exports and the government. There are several downside risks that could complicate things going forward.

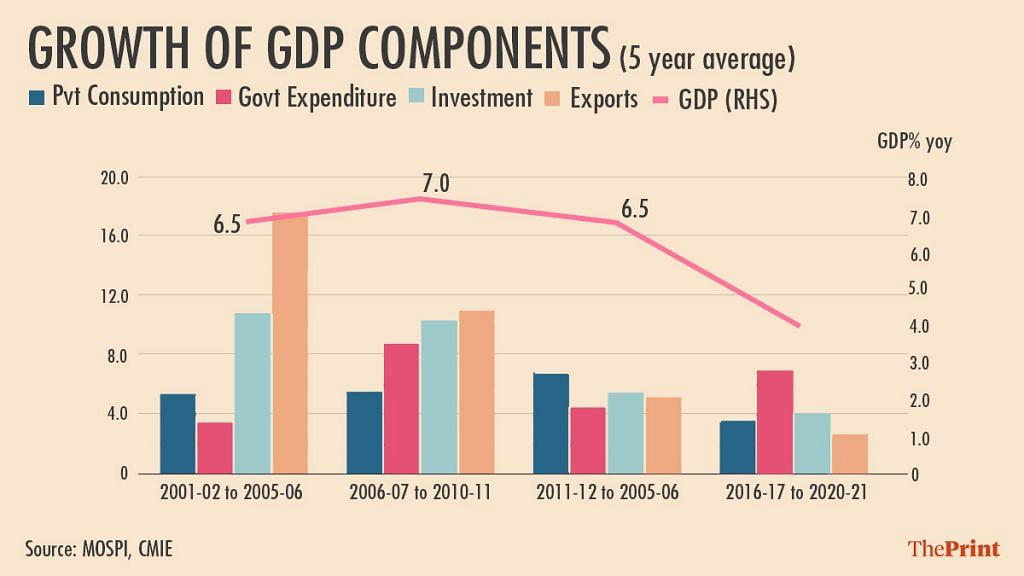

On the expenditure side, GDP has four components: consumption by households, investment by businesses, government spending on goods and services, and net exports. Historical data shows that Indian GDP has grown very rapidly when investment and exports have performed well. India’s investment-to-GDP ratio, which stood at 22.9 per cent in FY 2000-01, rose to 34.3 per cent in FY 2011-12, growing at an average rate of 10 per cent. Exports grew from 11.6 percent of GDP to 24.5 percent, an average growth of 15 percent over the period. No wonder, it is also a period of rapid GDP growth except for a brief intermission in FY 2008-09 due to the global financial crisis.

From FY2011-12 onwards, things started deteriorating – double-digit inflation pushed up input costs for businesses. Along with delays in approvals (policy paralysis), this made many projects commercially unviable and increased defaults in banks’ loans, adversely affecting their ability and willingness to finance new projects. As a result, private investment began to decline. The export-to-GDP ratio also began to decline after a growth of 25.2 per cent in 2013-14, an average growth of only 1.4 per cent during 2014-15 to 2020-21. The fall in exports and investment led to a slowdown in GDP growth, especially after the erroneous demonetisation, followed by the badly designed and poorly implemented GST, which ruined the prospects of small and medium enterprises.

To compensate for sluggish investment and exports, the Narendra Modi government started spending more. Thus, the share of government spending on goods and services in India’s GDP increased from 10 per cent in FY 2013-14 to around 11.7 per cent in FY 2020-21, an average growth of 7 per cent and an all-time high of 16.4 per cent. level reached. During the first quarter of the financial year 2020-21. The problem is that about 84 percent of the budgetary support is revenue expenditure. lower multiplier (0.99) the effect on GDP growth compared to capital expenditure or private investment (2.45). Also, how much government spending can be increased in a slowing economy when debt has crossed 90 percent of GDP. This is why the Modi government has resisted the temptation to spend more, despite India Inc’s pressure for more fiscal leeway. Instead, it is pressuring the Reserve Bank of India to do the heavy lifting.

If that wasn’t enough, the Indian economy was hit by the Covid-19 pandemic when it was already in recession Method. As a result, GDP declined by 7.3 percent for the first time in decades.

Read also: Indian economy needs to fire 4 engines to grow. But Modi government only 2. betting on

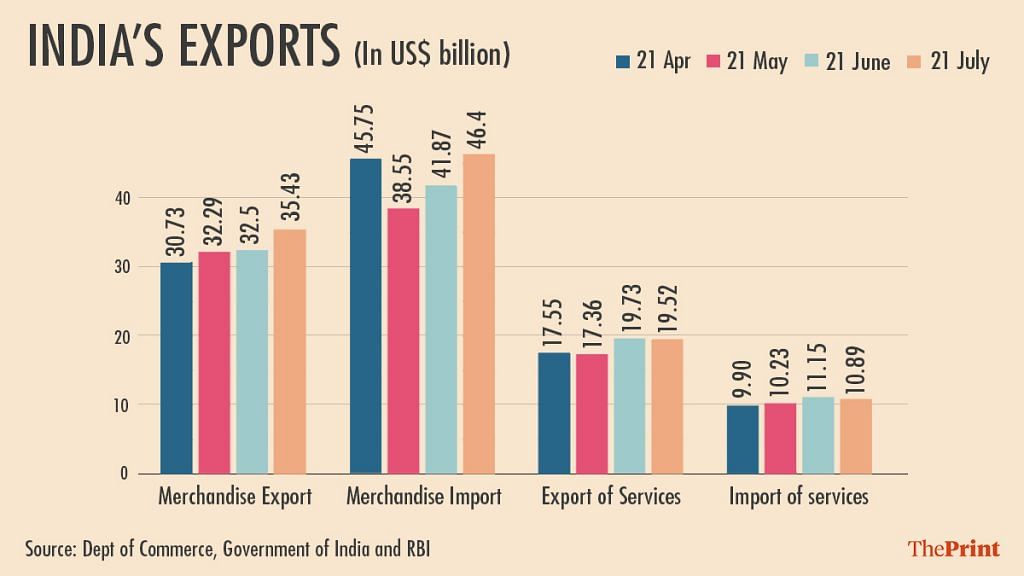

unexpected export boost

However, the Indian economy is receiving an unexpected boost from the external sector in the form of exports and equity investments from private equity (PE) and venture capitalists. India’s goods were exported hovering About $300 billion for almost a decade. However, in the first four months of the current fiscal year, India’s goods exports of $130.8 billion (compared to an average of $100 billion or more during 2010-20) accounted for a third (32.64 percent) of the country’s ambitious annual has done. $400 billion target despite container shortages and COVID-induced supply chain disruptions. Thus, exports (both goods and services) are providing much needed ‘demand side’ support to the Indian economy.

With strong exports, mostly foreign venture capital and private equity (PE) amounts exceeding US$ 20 billion in the first seven months of 2021. to make it available A big boost to the Indian economy which it desperately needs.

India’s goods imports are also increasing rapidly. Except for electronics and capital goods, Indian imports are mostly raw materials/intermediates such as ores and concentrates, crude oil and gold, or parts and components, which are further processed into value-added products, and a major part of this is exported. Is. Thus, rapidly increasing exports and imports could be a sign of rapid turnaround in the Indian economy, argue the optimists.

fault lines

Despite an increasingly supportive external macroeconomic environment, there are several domestic adversities that could play a bad game and derail India’s economic recovery. Although steady progress is being made, vaccination remains Weird. This should be a matter of grave concern, especially when the threat of a third wave looms large.

Unlike the first wave of the pandemic, the deadly second wave has hit rural India badly, with no real health infrastructure, especially in the poorer states of North and East India. The result is a sudden and substantial increase in out-of-pocket spending on health care, and in turn, loss of savings and increased indebtedness. This is bound to affect their demand for industrial goods and services as well as their ability to invest in agricultural operations. To make matters worse, there are concerns about monsoon rains (on which almost half of India’s gross arable land depends for irrigation), not in terms of total amounts, but their timing in various Indian states and in terms of distribution. NS erratic and uneven distribution of monsoon As a result, kharif acreage fell by 2.36 per cent till August 6, which would have an impact on the management of food inflation.

Moreover, weak consumer demand for discretionary goods and services and low capacity utilization have kept private investment muted for some more time and will continue to do so. Indian companies are focusing on margin improvement by cutting all types of costs – staff, marketing and promotion, and wherever possible, raw materials – to keep afloat. However, there is a limit to reducing raw material costs, amid a runaway commodity price inflation. Thus, everyone is trying to squeeze employees and small vendors, which will further adversely affect household income and demand for their goods and services.

However, there are some exceptions here. First, the relatively affluent section of the Indian working population. While there is some impact on salaried income due to cost-cutting in the corporate sector, and higher inflation leading to a further decline in purchasing power, other income, especially from investments in equities and mutual funds (which have between 10% and Rs. Tax is levied at lower rates) 15 per cent as compared to income from salary, which is taxed up to 42.77 per cent).

Second, there are neither job cuts nor salary cuts in India’s tech sector, including tech startups. Instead, companies are not getting enough employees despite willingness to pay generous salaries and perks. This can be seen in the boom attrition Rates among Indian IT companies in the first quarter of FY2022. Notwithstanding the fact that this section better affluent indian family is small (10-15 million), it will support demand for discretionary goods and services, including demand for premium housing. However, the demand for this segment is likely to be appropriated by large organized sector companies, which have pricing power. These are the companies that can To move on Part of the increase in input costs to consumers. Thus, most of the Capital Expenditure (CapEx) is happening and will continue to happen in this segment. A comprehensive CapEx recovery is too far in our opinion.

Overall, India’s economic recovery has been one-sided, but it is a positive story. The other two key engines – consumption and investment, which make up more than three-quarters of the Indian economy – are yet to improve. Similarly, we really can’t look away The sectors most affected by the disruptions caused by the pandemic – from the situation of informal sector workers and SMEs in the country. This will continue to limit India’s growth prospects going forward.

Ritesh K Singh is the CEO of @RiteshEconomist Indonomics Consulting Pvt Ltd. Steven Raj Padakandla @ pstevenraj1 is a Faculty at IMT, Hyderabad.

(Edited by Srinjoy Dey)

subscribe our channel youtube And Wire

Why is the news media in crisis and how can you fix it?

India needs free, unbiased, non-hyphenated and questionable journalism even more as it is facing many crises.

But the news media itself is in trouble. There have been brutal layoffs and pay-cuts. The best of journalism are shrinking, yielding to raw prime-time spectacle.

ThePrint has the best young journalists, columnists and editors to work for it. Smart and thinking people like you will have to pay the price for maintaining this quality of journalism. Whether you live in India or abroad, you can Here.