MMany politicians and political parties – especially incumbents – have contested elections in the name of stability and continuity. The claim that stability is a necessary condition for good governance is taken for granted. It is useful to examine such assumptions, especially in the context of state governments that have long-tenured chief ministers.

For example, the current chief minister of Odisha, Naveen Patnaik, has been in power since 2000. Whatever the merits or demerits of such unbroken and long tenures in an electoral democracy, the good thing is that it gives us the ability to measure governance. Clearly the consequences and hold those politicians responsible. Twenty-three years is more than double the average number of years a child attends school in India.

One aspect of the modern republic that makes it difficult to measure outcomes and hold them accountable to state governments is the increasing centralization of policy making. It is difficult to isolate the policy outcomes of state governments. But some aspects of governance are still basic functions of state governments; The most basic of these functions are in the areas of public health and education. Therefore, to measure the performance of Patnaik, who has been one of India’s longest-serving chief ministers, it is imperative to compare Odisha’s progress in health and education with other states over the last 23 years.

Read also: Madhya Pradesh is richer than Bihar. So why is it still lagging behind?

What do the IMR figures tell

A universally used metric to measure the health of a developing society is the infant mortality rate (IMR). As an indicator it is easy to measure, difficult to fudge and strong. In 1999, before Patnaik became chief minister of Odisha, the state had the worst IMR of 96.7 among large states. In 2020, the last year for which data is available, Odisha’s IMR was 36. It’s still in the lower half, but it’s not the worst in the least. Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh – two large regions with immense influence on national politics – are among the worst performing large states in 2020 with IMRs of 43 and 38. Madhya Pradesh, incidentally, is another state which has had a chief minister for a longer tenure.

But a closer look at the data reveals a troubling trend. Despite having a base effect advantage, the bottom half of India has not done well enough in terms of rate of improvement compared to better-off states. After all, it’s much easier to recover quickly from a bad situation than from a relatively better one. Odisha’s peers in IMR – Assam, UP and MP – are India’s least improved states in that metric. Odisha breaks out of this terrible company and does a little better in terms of its rate of improvement, but only just so.

Read also: The decline in the economy of West Bengal has been astonishing. passionate about agriculture

GER data analysis

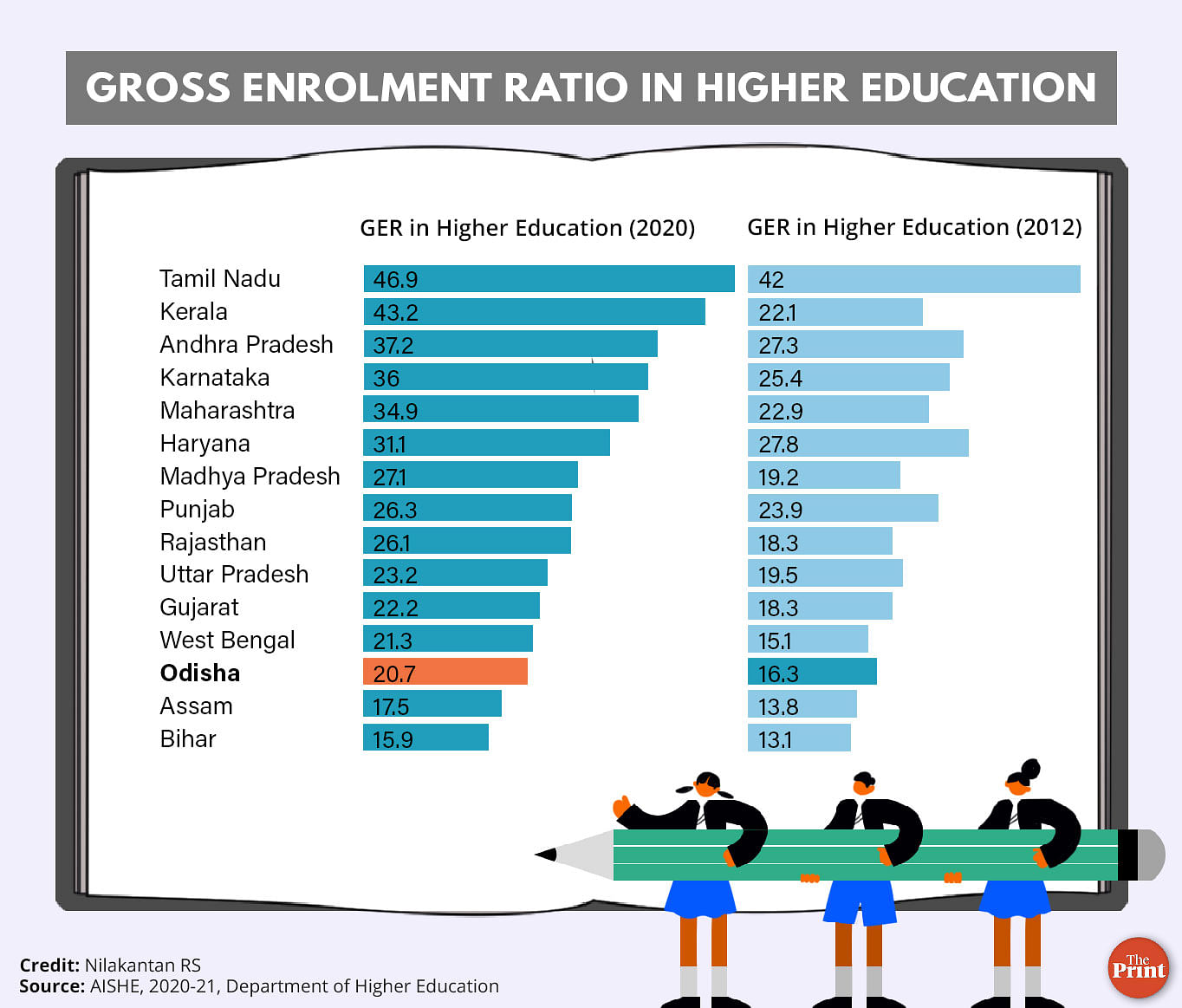

In education, another domain that affects basic living and which state governments still control, Odisha has maintained its modest performance. It is near the bottom and has not improved with such a low base warrant rate. The Gross Enrollment Ratio (GER) in higher education is a useful indicator of how well a society is doing in education. A high GER in colleges and equivalent institutions indicates a consistently high enrollment even in the lower grades, as children go through school to get into colleges. Odisha has lagged behind in this regard, with a GER of 20.7 in 2020, up from 16.3 in 2012. Bihar (the second state to have a chief minister for a long time) and Assam are the other two states that keep the Odisha Company.

An interesting aspect of the data in health and education is that MP appears to have made significant relative improvements in education while getting worse in health outcomes. A comparison with Odisha in these two important development area metrics shows that Odisha has better child survival rates, while Madhya Pradesh offers better prospects for development and higher education.

Similarly, Bihar has better outcomes in health than both Odisha and MP, while poor outcomes in education. All three of these states have had long-term chief ministers, but their rate of reform, while generally poor, has kept pace with the country, which makes it even more worrying. Why are chief ministers with long tenures unable to do much about the most basic aspects of their citizens’ lives?

In terms of overall economic outcomes, the story of Odisha is again no different. per capita of the state Income It was about two-thirds of India’s per capita income in 1999–2000. This ratio remained relatively in 2019-20 Fixed, In other words, Odisha maintained its relative position for the entire duration of Patnaik’s tenure. The story of Madhya Pradesh and Bihar is also not very different in terms of economic opportunities.

Odisha and MP receive more support for their state budgets through central transfers than they do from the revenue they generate themselves. Yet, their allocation to health and education, as a proportion of their budgeted expenditure, is indistinguishable from other states. This poses a simple question: why should rich states transfer their revenue to poorer states if they are not spending more on health and education as a result of additional transfers to poorer states?

A sober look at the data on health, education and economic outcomes indicates that Odisha and Madhya Pradesh are on cruise control, though near the bottom. They are not spoiled and can even improve a bit. But they are not improving at the rates typical of societies that have such poor indicators in every measurable area of governance.

Long and unbroken tenures are problematic in a democracy. Ideally, we want a system of governance where we don’t replace kings with elected versions of themselves. We want to imagine an egalitarian system where no one has a monopoly on power. More importantly, we want our politics to be an equal battle between competing ideas and viewpoints so that the best policy wins. This happens only when we try everything and its alternatives. A longer term is the antithesis of all those goals. However, the one thing it can achieve is policy continuity. And if we are willing to pay a heavy price for not being egalitarian or not having a marketplace of ideas, then for policy sustainability, incumbents must deliver governance results that far exceed the standard rate of progress. What the long tenures of Patnaik as chief minister, or for that matter, Mamata Banerjee, Shivraj Singh Chouhan and Narendra Modi, suggests is that they have nothing to show in terms of results of governance, while There is a lot to be said in terms of erosion of democratic values.

In short, the data confirms the wisdom of the people: always vote for the incumbent; It keeps them honest and us powerful.

Neelakantan RS is a data scientist and author of South vs North: India’s Great Divide. He tweeted @puram_politics. Thoughts are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)