Form of words:

Bangalore: It is 9.30 a.m. Tuesday, and in Bengaluru’s Bhuvaneshwari Nagar, second-generation handloom weaver S. Marudachala Murthy has called a meeting of parents to discuss school fees.

The annual fee for his eldest daughter in an institution run by a spiritual trust is Rs 70,000. The meeting is to build a consensus on requesting the school to waive 50 per cent fees, as the incomes of parents, some of them weavers, have been at an all-time low due to the pandemic, the subsequent lockdown and the toll. It has taken over the economy.

“The income from handloom had completely stopped last year. Today, there has been a recovery of around 50 per cent, but it will take a year or two for the industry to return to normalcy if there is no further lockdown,” Murthy told The Print.

Handloom weaving, one of the smallest components of textile micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), is a traditional craft run by families such as Murthy.

The micro-business suffered huge losses due to the covid pandemic and the lockdown, which reduced consumer demand, leaving the apparel industry as a whole.

Handloom owners suffered as many loom workers left for their hometowns and did not return. The looms lay idle, while the debt piled up.

According to data from the state’s new textile policy for 2019-2024, Karnataka accounts for 20 per cent of the country’s total apparel production, which is valued at $1.56 billion.

But textile factories in the state have had to lay off a huge amount of workers due to the pandemic. According to a study by Bengaluru-based Alternative Law Forum (ALF), many small units with hardly 500 to 1,000 employees have bentUnable to bear the financial loss. It has had an impact on the entire supply chain, from textile traders to loom owners and weavers.

However, with the normalization of demand, large garment factories have started working round the clock.

Read also: India’s MSME sector is the largest after China. But no one is talking about its role in emissions

handloom in trouble

The season leading up to Dussehra and Diwali is considered to be the busiest time for weavers, but this time it is not so.

Take the case of the idol itself. Barely a few years ago Murthy and her 75-year-old father CP Subramani There were 16 handloom owners and 14 workers were employed. Today there are four handlooms in an annexe hall next to his residence, of which only two are working. Murthy no longer weaves. His senior citizen father and another loom worker are in a business that is fast losing ground in Karnataka.

“Now there is no taker for this work. Weavers will instead take up jobs as drivers, salespeople, security guards as they get a fixed salary of at least Rs 10,000 to Rs 12,000,” said Murthy.

Hundreds of loom workers, he said, went back to their hometowns during the lockdown and never returned. Some have taken on other jobs or are attempting to keep up with subsidiary manufacturing.

Seventy-year-old Kulappa, who has been a handloom worker for 45 years, is among the few who have been engaged in business through the pandemic but for a modest income. He earns Rs 700 for each sari he weaves and around Rs 350 a day because “it takes about two days to weave a simple saree”. Kulappa said that if the saree he is weaving is for a shop in Karnataka, his wages are Rs 100 less.

As Kulappa goes about his business, oversees the 8,000 silk threads, weaves them into a sari 2,000 strands at a time, works the treadle with his feet on a pit loom, three more looms lying idle .

For Gunasekhar, whose family has been entirely involved in handlooms, the pandemic brought about a change. He discontinued the handloom and diverted his resources to a newly established motorized silk spooling unit. He said that with this move his business has increased by Rs 10,000.

However, not everyone is able to switch.

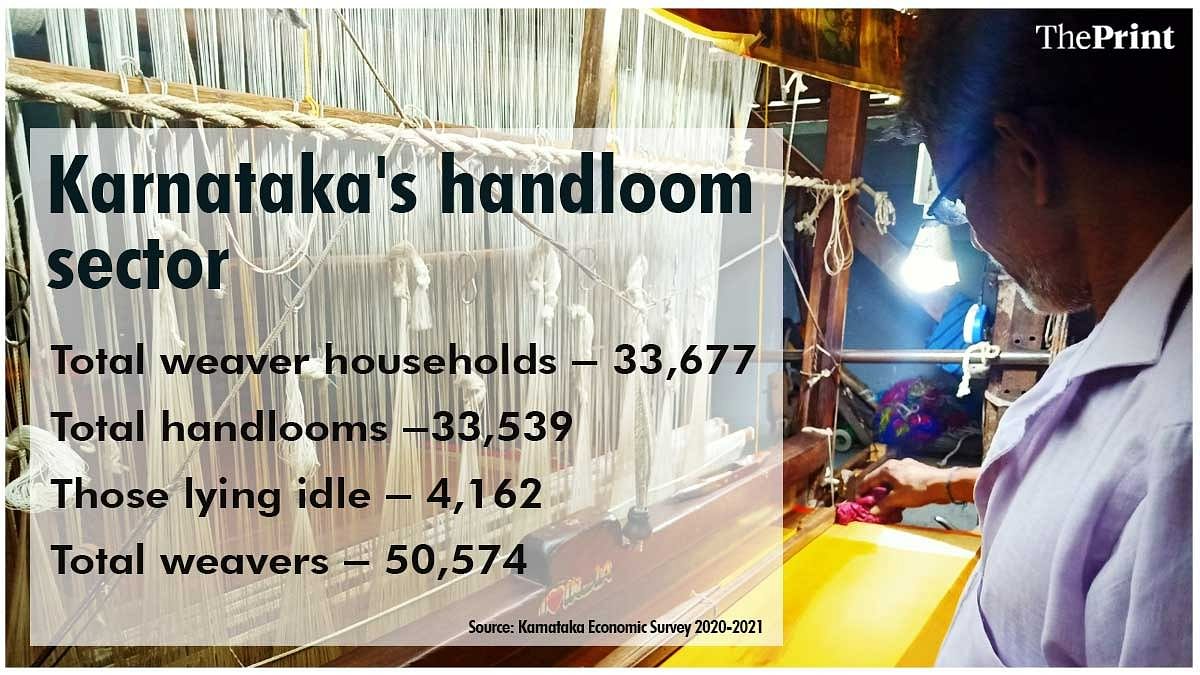

According to Karnataka Economic Survey 2020-2021, There are 33,677 weaver families in the state. There are also 33,539 handlooms, of which 4,162 are lying idle. As per the survey, the remaining 29,377 handlooms are being operated by 50,574 weavers.

During the pandemic, hundreds of them opted to go out of business. The state government’s efforts to help have not helped either.

Karnataka government announced a scheme in 2020 – Nekara Samman Yojana – to provide cash Help 2,000 for each registered weaver in the state.

Sudhir Kamat, founder of Shreni Samuday, an organization that works with traditional business groups in several states, said, “The scheme has not helped the loom workers who neither fit into the unorganized sector workers nor are they able to work in looms. are the owners.”

Kamat said the assistance was only for those registered with the government, adding that many loom workers are not registered with the government due to red tape and lack of clear classification of norms for issuance of registration numbers.

“The crisis in the region predates Covid but the pandemic has made matters worse. The lockdown has left loom owners with huge stocks of sarees that will not get remunerative prices, meaning distress sales. This has put the loom owners in serious debt,” he said.

“Unfortunately, the traditional loom workers, whom I call swadeshi workers, have neither control over the demand nor over the supply. They work on the basis of orders placed by the buyers. Most worryingly, they do not have market access or regular credit linked supply of raw materials.

Improvements in big companies, less expectation from small units

According to the State Economic Survey 2020-2021, the readymade garments sector employs 4,41,738 people in Karnataka. Karnataka’s total exports in readymade garments for the financial year 2019-2020 stood at Rs 15,707.11 crore, which is nearly Rs 200 crore less than the number for 2018-2019.

according to a Study Run by the Garments and Textile Workers’ Union (GATWU) and ALF, garment factories took a hit during the lockdown, which ultimately impacted employees.

Nine out of 25 factories in three garment clusters in Bengaluru in the study had to be completely shut down, resulting in about 5,600 to 7,200 workers losing their jobs during a pandemic. Sixteen factories surveyed had reduced in size, leading to the loss of 11,000 workers, the study said.

“We estimated that 60 per cent of garment workers lost their jobs without notice and under pressure. They were asked to resign and avail their dues or forfeit their dues,” Gatvu President Pratibha R told ThePrint.

He said the data received through the Department of Factories and Boilers shows that 65 factories in Bengaluru urban district were recorded as closed since April 1, 2020. “Thousands of workers who lost their jobs due to factory closures worked in units that had less than 100 workers,” he said.

Pratibha said things started to look up after the orders came back in November 2020, but the revival is limited to large apparel factories only.

“There is a lot of work now but there is a shortage of laborers as many have gone back to their hometowns and are not ready to return. Large factories are working 24/7 and are willing to pay extra even on weekends. Since the workers are in dire need of money, they are doing jobs,” said Jayaram KR, legal advisor at Gatvu.

He said that due to the closure of businesses and shops, the stock kept for a year has been sent back to the factories.

There is a concept called “Back to Warehouse” where garments that are not sold within a year are returned to the factories. Since exclusive retail outlets of foreign brands were out of business, the stock has been sent back,” said Jayaram.

“Garment factories are selling them to non-branded stores, where they are being sold at cheaper prices. I could never buy an arrow shirt as it costs around Rs 3,000-4,000, but I recently bought three arrow shirts for Rs 350 each.

Double whammy for small and medium businessmen, traders

Sitting in his shop in Chickpet, one of Asia’s largest textile markets, Sajjan Raj Mehta told ThePrint that his area has seen a 60 per cent recovery so far.

“We are a fashion and utility-based business. There is no demand from the closure of schools, offices, colleges, travel, parties, functions, social events,” he said. “People’s income has gone down and whatever money they have, they want to save for medical expenses and household expenses. Some demand has come back in the last four months itself.”

Mehta, who is also the chairman of the taxation committee of the Karnataka Hosiery and Garment Association (Khaga), told ThePrint that the apparel sector would face further setbacks due to a new proposal of the 45th Goods and Services Tax (GST) Council.

The proposal intends to correct the existing inverted tax structure and bring all goods in the 12 per cent slab from January next year.

Presently GST Slabs under Textiles Clothes Five percent and 18 percent for man-made fiber and 12 percent for man-made yarn. Garments costing less than Rs 1000 attract 5 per cent GST while those above Rs 1000 attract 12 per cent GST.

The government is considering bringing all clothing in the 12 per cent slab, irrespective of the cost.

The incumbent inverted tax structure forces the government to refund the inverse input tax credit that accrues when the tax on the final product is less than the tax levied on the input. For ExampleThe GST slab for finished leather footwear priced below Rs 1000 is 5 per cent. But the GST slab for inputs for manufacturing of footwear is up to 18 per cent. The government refunds around Rs 2,000 crore annually to the footwear sector.

“It would be suicidal,” Mehta said. “Dozens of garment traders in this area alone have closed shops unable to bear the loss during the lockdown. If the GST Council decides to tax all items under the readymade garments and textiles under the 12 per cent slab, irrespective of the selling price, we will be over.

Moreover, rising cotton prices and rising fuel prices have made survival difficult for many textile traders, who are already reeling under demand and losses, affecting transport.

One such cloth merchant, Gautam Chand Porwal, had to reduce his business. “I used to supply kids clothes all over South India but that got reduced earlier in Karnataka and now I can supply only to Bengaluru. Input cost has increased by 20 per cent. Business has declined by 60 percent since the lockdown. All I can do is be patient,” Porwal said.

Some others have managed to keep their businesses afloat by innovating and revamping.

Dungarmal Chopra, president of Khaga, is one such entrepreneur. “I run a manufacturing unit where school uniforms are sewn and I also supply them, but during the pandemic, it came to a grinding halt. To protect myself, I had to convert my factory into a mask-making unit,” he said. “No profit but it saved me from closing shop.”

(Edited by Arun Prashant)

Read also: ‘Process is punishment, govt loves paper’: MSMEs call for uncomfortable doing business in India

subscribe our channel youtube And Wire

Why is the news media in crisis and how can you fix it?

India needs free, unbiased, non-hyphenated and questionable journalism even more as it is facing many crises.

But the news media itself is in trouble. There have been brutal layoffs and pay-cuts. The best of journalism are shrinking, yielding to raw prime-time spectacle.

ThePrint has the best young journalists, columnists and editors to work for it. Smart and thinking people like you will have to pay a price to maintain this quality of journalism. Whether you live in India or abroad, you can Here.