Form of words:

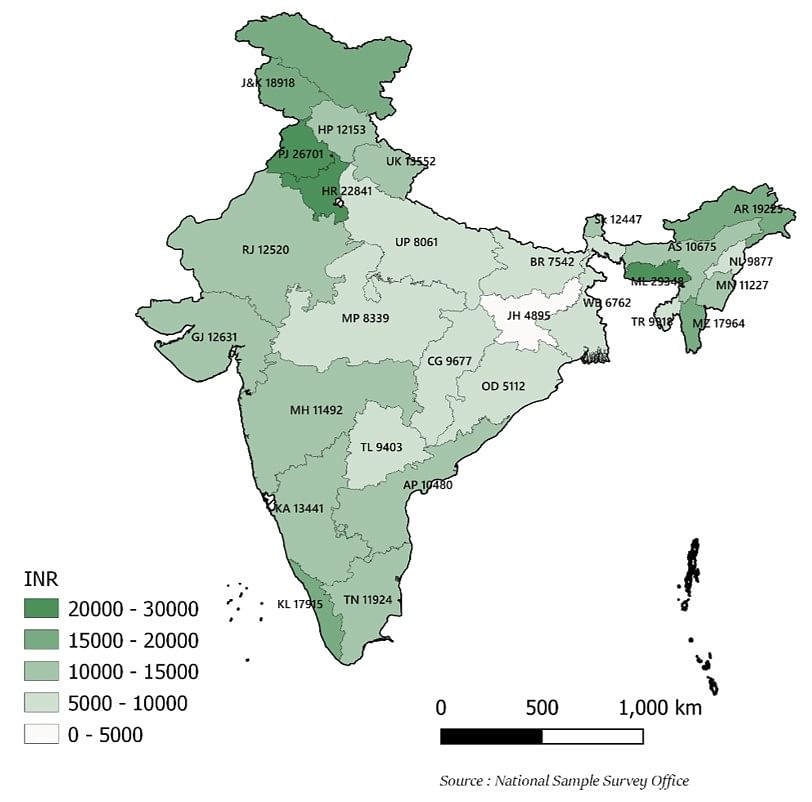

nThe farmers of Punjab, but the farmers of the northeastern state of Meghalaya are now the richest in India. This is according to the recently released survey report of the Government of India titled ‘Agricultural households and land and household holdings in rural India, 2019’. According to this report, in 2018-19, an average farming family in Meghalaya earned around Rs 29,348 per month, while a farmer’s family in Punjab earned around Rs 26,701 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: State-wise Monthly Farmers’ Income 2018-19

Jharkhand, Odisha, West Bengal, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh recorded the lowest farmer income. In fact, the sum of the total income earned by farmers in the four states of Jharkhand, Odisha, West Bengal and Bihar is less than the income of a farmer in Meghalaya or Punjab.

In a series of articles to follow, we aim to decode this survey data in detail. In this short article, I track basic trends in farmer incomes for major agricultural states. But first just a little context of the data.

data on farmer income

Just as India does not have an official estimate of the number of farmers in the country, there is no annual estimate of the level of income earned by them. This number is estimated through farmer surveys conducted by the National Statistical Office (NSO), usually every 10 years. As of today, the latest farmer income estimates from NSO are available for three years: 2002-03, 2012-13 and the recently released 2018-19.

Apart from this, there is another estimate on the income of farmers from NABARD, which conducted its NABARD All India Rural Financial Inclusion Survey (NAFIS) in 2016-17. This survey gave the income levels of farmers for 2015-16. However, there is one thing to be careful of while comparing NSO’s farmer income data with NAFIS. Unlike the NSO, NAFIS uses a more comprehensive definition of rural areas, which is likely to cause an upward bias in estimates. In other words, if NAFIS had followed the same definition as NSO, then farmers’ income estimates in NAFIS would have been lower than the reported estimates. Nevertheless, we compare the trends in farmers’ income over four time periods.

Read also: NSS survey on farmers is the mid-term report card of Modi’s promise, with ‘fail’ written on it

Indian average

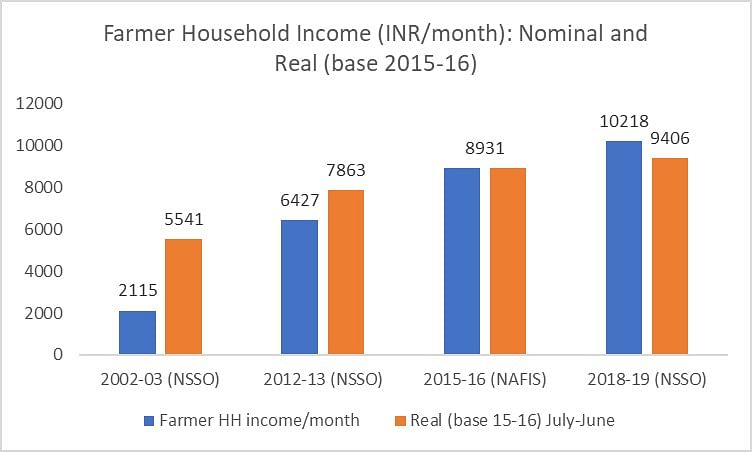

According to the NSO, an average Indian farmer family earned around Rs 10,218 per month in 2018-19. This price was Rs 6,427 in 2012-13 and Rs 2,115 in 2002-03. In nominal terms, this translates to an average annual growth rate of about 10.3% between 2002-03 and 2018-19 and about 8% between 2012-13 and 2018-19 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Trend in All India Income

In real terms (Base 2015-16), the income increased from about Rs 5,541 in 2002-03 to Rs 7,863 in 2012-13, to about Rs 9,406 now. This translates to an average annual growth rate of about 3.4% between 2002-03 and 2018-19 and about 3% between 2012-13 and 2018-19 (Figure 2).

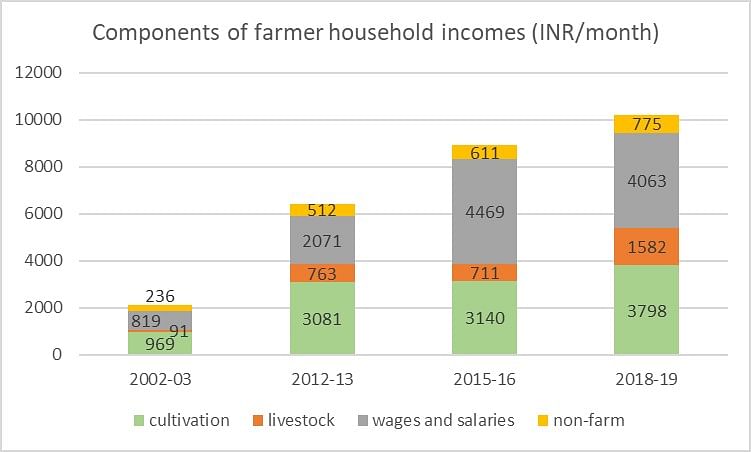

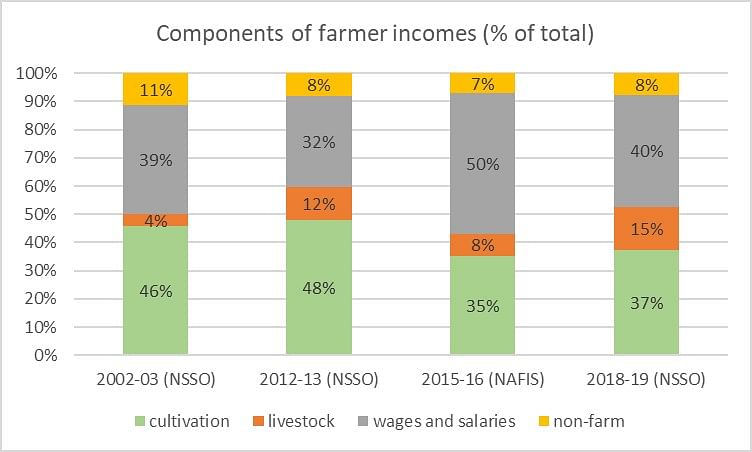

Farming income is the only source of income for a farming family. According to both NSO and NAFIS, farmers have four main sources of income: (i) farming activities, (ii) livestock rearing and related activities, (iii) wages and salaries earned by working under schemes like MGNREGA, or others. farm or any other job; and (iv) non-farm activities (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Trends in the All India Composition of Farmer Income

Note: For 2018-19, income from leased land is added to ‘non-agricultural’ income

Note: For 2018-19, income from leased land is added to ‘non-agricultural’ income

As per Figure 3, it appears that in 2018-19, a farmer earned about Rs 3,800 from farming, more than Rs 4,000 from working as a laborer or labourer, about Rs 1,580 from livestock activities and about Rs 1,580 from non-farm activities. Earned approx Rs 775. .

Comparing the data between the years shows two trends, Always,

- Farmers are earning more from activities other than farming. In 2018-19, about 55% of the income of the farmer family came from livestock activities and wages and salaries. This contribution was very low at around 43% in 2002-03 and 44% in 2012-13;

- In fact, it appears that the income from agriculture has fallen for an average farming household between 2012-13 and 2018-19. In 2012-13, a farming family earned about Rs 3,769 per month from farming, but in 2018-19, the income from farming declined to Rs 3,496 per month.

Read also: Don’t get caught in the battle of MSP. India must move to end inequality in WTO laws

State wise Trend in Farmer Income

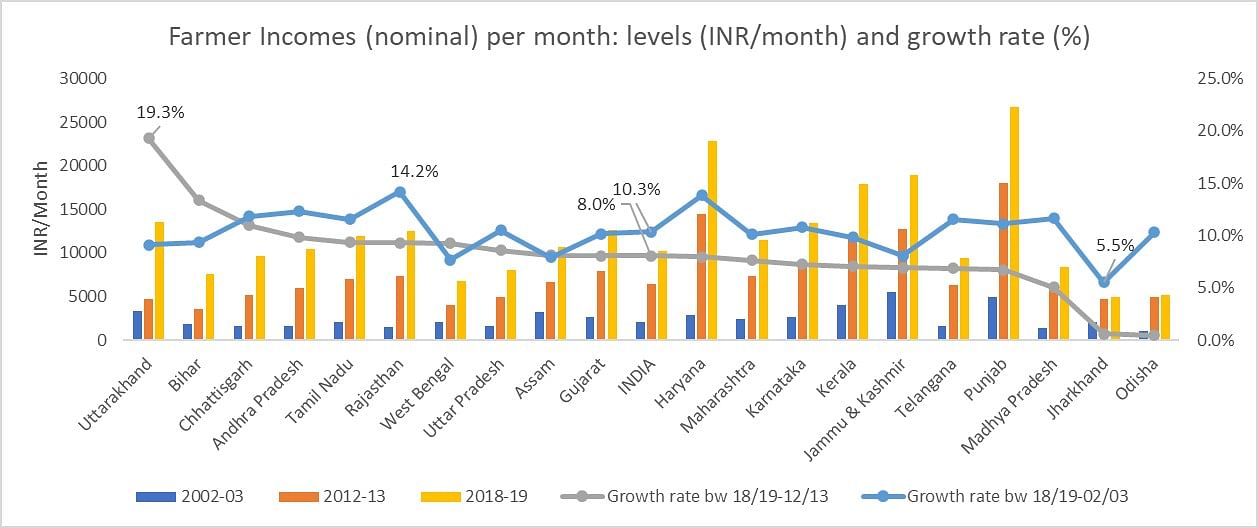

Among the major agricultural states, it appears that in the 16 years between 2002-03 and 2018-19, Rajasthan has the fastest nominal income growth rate (14.2%) and Jharkhand has the slowest (5.5%).

Figure 4: State-wise Trend in Farmers’ Income (Select Agricultural States)

However, between 2012-13 and 2018-19, Bihar (13.3%) and Uttarakhand (19.3%) have shown the fastest growth rate and Odisha (0.5%) and Jharkhand (0.6%) the slowest.

Odisha is an interesting case. Between 2002-03 and 2012-13, farmers’ income in Odisha grew the fastest in the country at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of about 16.7%, but since then the growth rate has been the lowest in the country. at 0.5% (between 2012-13 and 2018-19).

Conclusion

A preliminary analysis of the NSO data for 2018-19 shows that farmers’ income has grown at a much slower pace than expected. In February 2016, Prime Minister Narendra Modi pledged to double farmers’ income by 2022-23. According to Dalwai Committee report goodThis doubling of income requires real farmer income to grow at a CAGR of around 10.4% between 2015-16 and 2022-21.

However, between 2015-16 and 2018-19, if one compares the NAFIS farmer income estimate with the NSO, it appears that farmers’ income has grown at a CAGR of around 1.7% in real terms. If farmers’ income is yet to be doubled by 2022-23, the required growth rate should be much higher at 13-14% per annum from 2018-19 to 2022-23.

Shweta Saini is Senior Fellow (Visiting) at ICRIER, New Delhi. He tweeted @shwetasaiini22. Thoughts are personal.

(edited by Prashant)

subscribe our channel youtube And Wire

Why is the news media in crisis and how can you fix it?

India needs independent, unbiased, non-hyphenated and questionable journalism even more as it is facing many crises.

But the news media itself is in trouble. There have been brutal layoffs and pay-cuts. The best of journalism are shrinking, yielding to raw prime-time spectacle.

ThePrint has the best young journalists, columnists and editors to work for it. Smart and thinking people like you will have to pay a price to maintain this quality of journalism. Whether you live in India or abroad, you can Here.