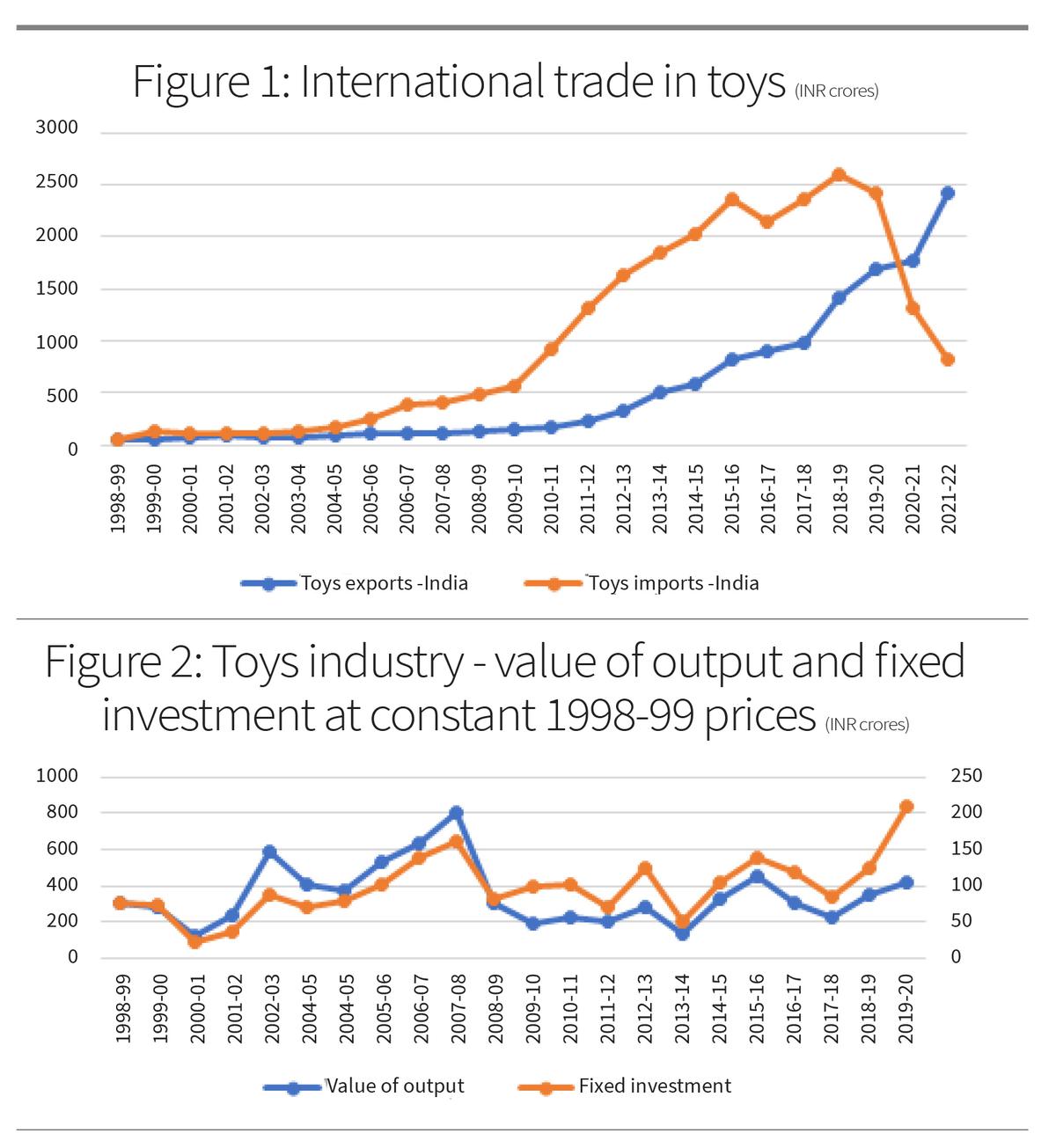

India has recently become a net exporter of toys (see graph), ending decades of import dominance during 2020-21 and 2021-22. Between 2018-19 and 2021-22, toys exports increased from $109 million (₹812 crore) to $177 million (₹1,237 crore); Official data showed imports fell from $371 million (₹2,593 crore) to $110 million (₹819 crore). These facts are undeniable. They can be cross-verified by mirror images of trade figures from the respective importing or exporting countries.

This achievement is widely attributed to the ‘Make in India’ initiative launched in 2014 and related policies, official press releases say. Furthermore, in 2020, Prime Minister Narendra Modi reportedly talked about promoting toy manufacturingIn his talk show ‘Mann Ki Baat’. What can explain such a rapid change in the toy business? Does it represent sustained growth in investment, production and efficiency gains, fueled by policy reforms? Or is it a short-term result of protectionism and global disruptions related to the COVID-19 pandemic?

import more than export

India’s toy industry is negligible. In 2015-16 (latest available figures for organized and unorganized sectors), the industry had about 15,000 enterprises or establishments, producing toys worth ₹1,688 crore using fixed capital of ₹626 crore at current prices and 35,000 Used to give employment to the workers. Registered factories – those employing 10 or more workers on a regular basis – account for 1% of the number of factories and enterprises, employ 20% of workers, use 63% of fixed capital, and produce 77% of the value of output We do. However, during the decade and a half between 2000 and 2016, industry output halved in real (net of inflation) with job losses. Till recently, the share of imports in domestic sales was up to 80%. Imports grew almost three times more than exports between 2000 and 2018-19.

India barely figures in the global toy trade, accounting for only a half-percentage point of its exports. Between 2014-19, the Indian toy industry witnessed negative productivity growth. So, what explains the rapid turnaround in the toy business in just three years? Basic custom duty on toys (HS code-9503) on imports tripled from 20% to 60% in February, 2020. Several non-tariff barriers were also imposed, such as the Production Registration Order and the Security Regulation Code, which contributed to import shrinkage (Press Information Bureau Release July 5, 2022,

Therefore, the question must be asked: do net exports represent a permanent improvement in industrial capacity and performance contributing to import contraction, or are these the short-term effects of protectionist measures? The question deserves attention because toy manufacturing, a labor-intensive industry, has always played an important (and perhaps extraneous) role in policy discourse.

asian scene vs india

Historically, successful industrializing countries in Asia have promoted toy exports to create jobs, starting with Japan nearly a century ago, China since the 1980s, and Vietnam currently following in their footsteps. However, India followed an inward-oriented industrial policy in the planning era, which sheltered domestic production by providing “dual protection”—import duties and reservation of the product for exclusive production in the small-scale sector—as Known as “Reservation Policy”. the outcome? Toy manufacturing remained stagnant, antiquated, and fragmented, despite a boom in imports of modern, safe, and branded toys. As many critics of India’s industrial policy have contended, this industry epitomizes everything that was wrong with misguided industrial policy.

Read this also | toys of our country

The reservation policy was abolished in 1997 in the wake of liberal reforms. As expected, new firms entered the organized sector, but only for a short period of time, and productivity growth recovered. But the unorganized sector was grappling with job losses even as most workers remained there.

In a recent study (India’s Toy Industry: Production and Trade since 2000, Economic and Political Weekly, May 6, 2023) We re-examined industry production and export performance from around 2000, with a new firm-level dataset from the formal and informal sectors synchronized with four-digit product-level trade data to be done. , In particular, we looked at how recent policy initiatives like ‘Make in India’ have impacted the toy industry.

we found (see graph) that after peaking in 2007-08 the annual value of output and fixed investment at constant prices (net of inflation) has moved downwards with considerable volatility (except in 2019-20). Clearly, there is no evidence of ‘Make in India’ having a positive impact on these indicators on a sustainable basis. The output of the informal or unorganized sector shrank, although it accounts for most of the establishments and employment.

Despite initial positive trends, industry dereservation (though it helped formalize the industry), failed to sustain production, investment and productivity growth after 2007-08. Contrary to popular belief and official claims, ‘Make in India’ had negligible impact in strengthening toy production and exports on a sustained basis.

in frames | toy Story

Versatile Crafts: From horses and dancing dolls to figurines of gods and goddesses, Kondapalli toys come in many forms.

Folklore: An artisan paints a toy bullock cart, part of a rural life exhibition.

Raw Material: The process of making Kondapalli toys, named after a famous village in Andhra Pradesh, begins with the cutting of Teela Ponki wood.

Touch of the Sun: Cut pieces of wood are laid out to dry in Kondapalli village.

Meticulous Carving: Artisans begin carving the toys.

Shaping: The softness of the wood allows for easy carving and fine detailing.

Team spirit: Families often sit together when making toys.

Dance Debut: This Kondapalli doll is all set to be a part of the Kolu display.

Old Tales: Many of the toys in Kondapalli are based on mythological characters.

Off to Market: The detailing on toys makes them a connoisseur’s delight.

1,3

it’s too early to claim success

As the reported change in toy exports is based on data from the most recent two years, and during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is perhaps too early to claim a success of the policy. The chances of maintaining net exports appear slim as the industry has hardly made sustained investments to boost production and exports.

In short, India’s export surplus in toys during 2020-21 and 2021-22 is a welcome change. However, it appears to have been driven by a rise in protectionism and the extraordinary circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic. This metamorphosis does not appear to be the result of strengthening domestic investment and production on a sustained basis. Since about 2000, the industry has shrunk with imports rising until two years ago. Though minuscule, as industry has a large role to play in policy discussions, the study offers valuable lessons. Neither the reservation policy during the planning era nor its abolition after the liberal reforms boosted the performance of the industry. One should perhaps look beyond simplistic binaries – planning versus reforms – and examine the ground reality of industrial locations and clusters in order to devise policies and institutions to nurture such industries.

Abhishek Anand is a consultant with PricewaterhouseCoopers, Dubai. R Nagaraj is a former professor of economics. Naveen Thomas teaches at the Jindal School of Government and Public Policy, OP Jindal Global University