Deepti Naval’s A Country Called Childhood is both a memoir and a commentary on life in the late 20th century

Deepti Naval’s a country called childhood is both a memoir and a commentary on life in the late 20th century

Deepti Naval’s new book, a country called childhood, has a unique quality of uniqueness and universality. On one level, the work of the famed actor-writer-illustrator is an autobiography—an apparently indulgent look at the innocent early years, the days spent playing with his older sister, Bobby, and the nights spent at his home in a quilt with a book. Spent under Chandravali, Amritsar. It is about girls and their alluring charm, and small escapes to watch the latest Rajesh Khanna or Shammi Kapoor starrer film in theatres.

On the other hand, it beautifully paints the picture of Amritsar in the 1950s and 60s, a city at peace in itself. She brings to the fore the cracks and pits of the socio-cultural canvas of the city: the plight of a well-educated middle-class man and his inability to get a job according to his qualifications; a city where Brahmins interact with the cobbler community, but from afar; of living next to a mosque – she calls it Masit (For Mosque) in typical Punjabi way — where muezzin invited prayer through them azaan And where, unlike now, female worshipers were welcomed.

a country called childhood

The book begins with his birth on a stormy night in 1952, and readers travel with him to America (following his father, who had moved away sometime earlier) and immigrant life across the ocean. And, of course, much is devoted to motivating her to get in front of the camera (though she remembers her grandmother saying, ‘Little girls from good families never leave Cinema on the road”).

Naval70, takes some questions from The Hindu’s Sunday Magazine, Edited excerpt:

The book is an autobiography and an essay on Amritsar and Indian society.

This is my tribute to the City of Golden Temple. In a way, I accept the city and everything it has given to me, which I will later become. I think those 19 years had a lot to contribute to.

Talking about those 19 years, there is no bitterness. And because you were born immediately after the split.

We were not fed any bitter truth. Our parents did not talk to us about partition and murders. We only heard about it here and there. Everyone knew about the massacre on both sides, but my parents didn’t talk much about it.

Was it a conscious decision?

Yes I think so. My father had a cousin who was kidnapped and killed in Beas. He never talked about it. We will hear from outside the Lahore massacre which began four months before the Amritsar massacre. For a while I grew up thinking that Muslims are cruel people. When I became a girl, our tenant above said to me, ‘ Son, the same thing has happened in both the ways, here also Katal-e-Aam and there also [child, this is what happened on both sides, there were mass killings here and there], No one spared each other, it was a bad time.

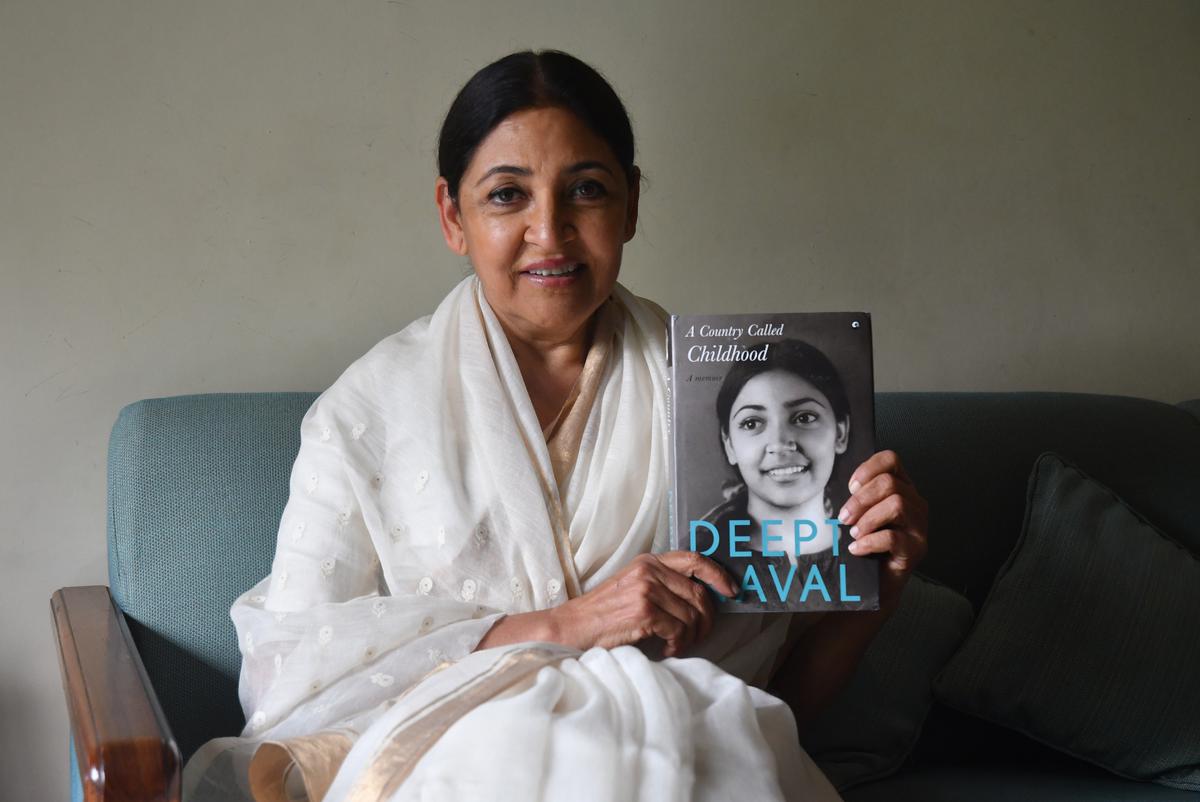

Deepti Naval. with a copy of a country called childhood, Published by Aleph Book Company | photo credit: Sushil Kumar Verma

Your father narrated a touching story of the mosque next to your house.

Yes, it happened four days before the Jallianwala Bagh incident. [in 1919], The British had killed about 25 people of different religions. The bodies of Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs were taken away Masit to perform his last rites. In retaliation for the deaths, a Jalsa [function] was held. I heard this story in my childhood.

Wasn’t this sad story affirming a kind of shared life where your religion didn’t matter?

yes we agreed Masit a place of worship. We used to think that just as Sikhs have the way of the Guru Granth Sahib, Muslims have their azaan And Namaz, As kids, we thought Masit We had ours next to our house too. we were listening azaan five times [a day], It became a part of our life. There was an acceptance of all aspects of the faith.

You talk about aiming to go to the JJ School of the Arts in Mumbai, but your parents couldn’t send you. A career in films was also a no-no. And you mention a friend who was not allowed to do Kathak in public. Was there a constant denial of opportunity to the girl child in the society?

My father could not afford to send me to Bombay; We didn’t have funds. I learned Kathak, but I could never use the skill in Hindi cinema. As far as denial of opportunities to girls was concerned, my mother was inclined towards art, but my grandmother could not pursue it despite being progressive. My mother has been a refugee twice – first from Burma and then from Lahore. My grandfather took ₹1 coin as dowry, as a token that we don’t believe in dowry system or idol worship. We are Arya Samajis; We believe in the intangible God. No other rituals. But even after all this’ What will People Say [what will people say]The ‘ aspect was still strong.

Actor-writer Deepti Naval | photo credit: Sushil Kumar Verma

You have mentioned in your book that ‘girls from good families do not go to the cinema’. Nevertheless, you went to many …

As a little girl of four, I was found staring at half-torn posters outside a cinema and my grandmother scolded me for it. [But] I have seen many movies While bunking class with the girls. We only visited Chitra Talkies, Adarsh Talkies, Nandan Cinemas etc.; We have never been to lazy people.

Did seeing Meena Kumari and Sadhna on screen sow the seeds of cinema in you?

Yes, I have felt it from the beginning. I was in love with Meena Kumari and then Sadhna. I loved his edge. I also had fringes. i thought work done by artists was so important. They were connecting with us emotionally. and i wanted to do that, [so] People will start recognizing me. They must think that I am speaking their mind.

Did your middle-class upbringing become a hindrance?

Yes, I had assumed that I would not get permission from my parents to appear in films. It was fine to be a classical dancer and perform on stage, but movies were for the masses. Later my entire family settled in America and I had to come to India alone. I was from Amritsar, and there was no family support in Bombay.

At the end of the book, you speak of your family’s departure for America, using the analogy of pigeons on the dome of a mosque, briefly arriving, then flying away. Did you like your story?

Yes it did. I used to see these pigeons on the dome of the mosque. They would fly away, but come back after a while. I also came back – not Amritsar but Bombay.

So was it fair that the first movie you heard was the story of Ruskin Bond’s Flight of Pigeons?

yes of course. Shyam became Benegal Passion,