twelve years ago, i discovered rabbit with amber eyesa memoir by celebrated British ceramist Edmund de Waal, in a bookshop in Edinburgh. It was another year before I read it and it became my favorite book of all time. Over the years, I’ve gifted it to friends, family, people I met at work, and often strangers. I have given over 300 copies to people whose lives have been enriched by its story in return – 264 Japanese in heritage netsuke (figure of carved wood or ivory, used as a toggle to attach a pouch to a garment) was collected by Charles Ephrussi, a beloved great-uncle, and associated with his family history who survived World War II by migrating around the world. De Waal is the great-grandson of Viktor von Ephrussi, a banker in Vienna who fled the city in 1938 after Hitler incorporated Austria into the Third Reich.

Thereafter, de Waal took a break from his commitments to research, travel and visit the sites of his Jewish family’s fortune/misfortune. their displacement is tied to netsuke Collection, which went through peoples and cities. Seven years of research took place before the book was published in 2010. Since then, “not only a story of anti-Semitism and racism”, as he said in a the new York Times The interview, “But Polarization, and the Treatment of Deportation, and Migration”, has been translated into over 30 languages and had an unprecedented print run of over two million copies.

The rabbit with amber eyes on display at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna

A decade later, during the pandemic, de Waal, who had recently been awarded the Isamu Noguchi Prize (which recognizes individuals with a spirit of innovation and creativity), decided to write another book, letter to commando, many people from Rabbit, it also uses objects—art and artifacts collected by Count Moisse de Camondo, Charles Ephrussi’s neighbor in 20th-century Paris—to tell a story that explores the Jewish heritage of its characters. Investigates. Their others in the various cities where they set up their highly successful businesses as well as memories are evoked and examined.

The book is written as a series of 58 fictional letters to Camondo, describing his life and death, his home and collections, his world and what it is about. During the pandemic, de Waal says he used to talk loudly to Camondo in his studio, and laughs that he was really lucky there was no one there. I had a chance to meet de Waal in Jaipur earlier this year, after visiting Vienna, where the major part of the story is based – seeing the building and the café mentioned in the book – and we had a long chat. Edited excerpts:

Edmond de Waal with Ruth Ojeki at the 2023 Jaipur Lit Fest

, Photo Credit: @edmunddewaal

Digging history requires a certain mindset and rigor. How does it work for you?

I am passionate by nature. It takes many forms for me, so whatever I take in I have to eliminate. Inherited these items from my great-grandfather, where they were and its effects, I wanted to know. Even though I told myself it would be a few months, it took seven years — digging in libraries and archives, but even more so, trawling the streets of Odessa, Vienna, Paris, and Tokyo in search of this story.

How did you separate yourself from the pain of others in the Jewish diaspora?

When you’re doing research, you’re writing things down. In my case, touching things, seeing places and buildings. And then there are moments that are really profound, your realization of the reality of what happened, and how terrible this breakdown in society was. In Paris and Vienna in 1938-39, only then did the second incident happen. Absolute terror when you know your friends are seeing right through you. You are seen as someone who does not belong – not as a friend, neighbor or colleague. These moments happen for the whole Jewish community [both] Books.

Edmond de Waal at the Musée Nissim de Camondo in Paris

, Photo Credit: @edmunddewaal

How close can a writer get to historical truth through memory, archives and stories?

It is completely layered. My manifesto was that if others before me had been so careful about the collection I had inherited, I would have to be equally careful in return. [So] Check, check, check. Stories from my father, grandmother and great-grandparents were always in flux. Stories change and depend on the truth people tell — what matters in that context and time. I have to tell stories with commitment as a writer, so I have to put these different truths on a powerful threshold. Marginality, to me, is the ability to look both ways: backwards and forwards. Worthwhile effort to understand the truth.

Both books talk about collections, whether they are in museums or scattered.

There’s a beautiful tension in putting things together and putting them together. My great grandfather Victor collected incredible books from the 16th and 17th centuries. Charles Ephrussi, the original collector of netsuke, who was my great-grandfather’s cousin, brought him to his family. You collect for your family, your community, your city or your country, but they will eventually fall apart. What are you handing over? There is also the question of the person who inherits and who asks: ‘What exactly am I inheriting and why?’ Collectors are a really important trope of people.

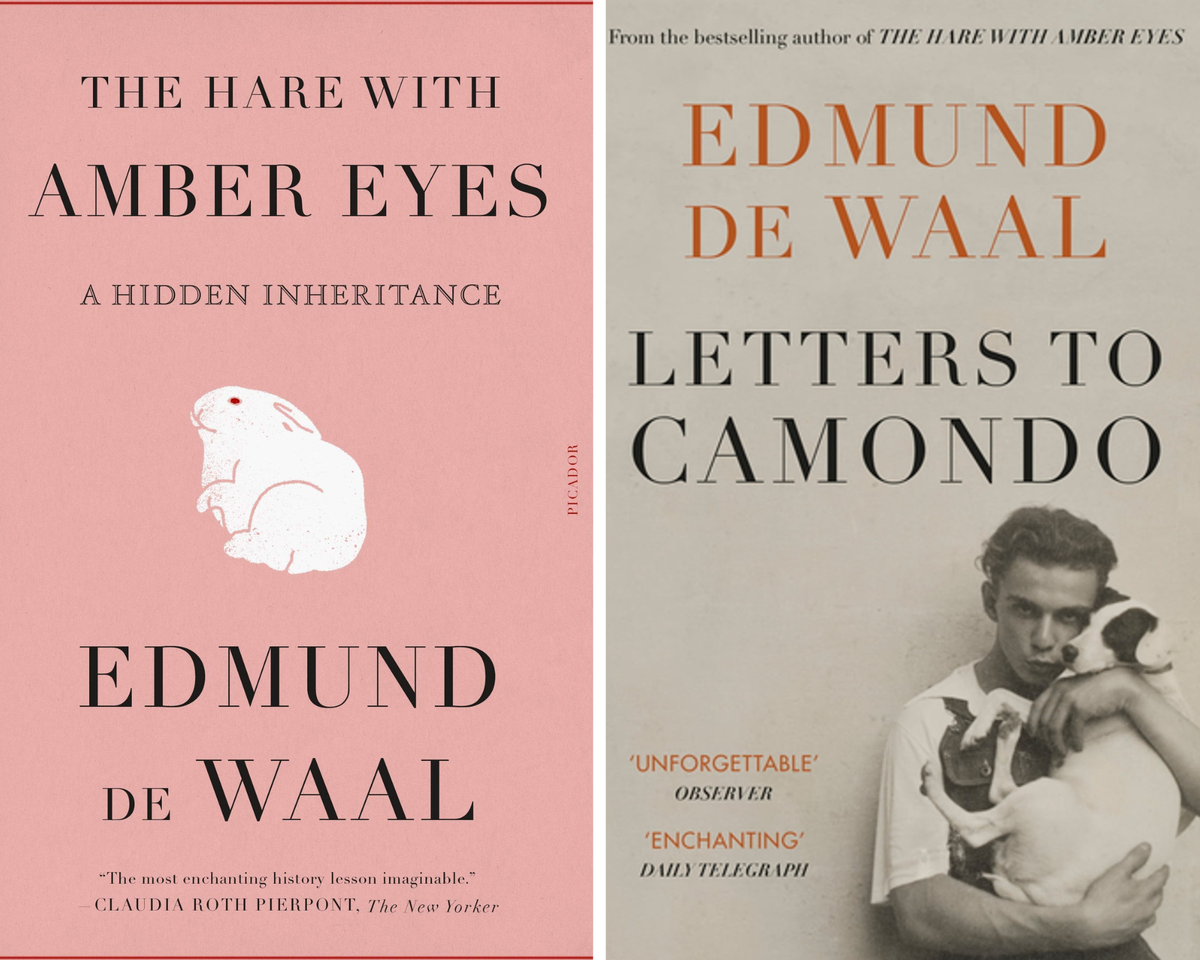

Book covers of ‘The Hare with Amber Eyes’ and ‘Letters to Camondo’

What about your ceramic work?

I try to inspire them by my mood and the music that I listen to and naively hope that they will be put together as a collection. They can be broken down, acquired in a museum, or placed in storage. I feel like I can’t control anything except the process of making them.

The joy of writing versus the joy of throwing pots.

They both are equally important to me. Making pots is an iterative immersion, very close to the music I listen to. It’s a way for me to pace the world. Writing is a passionate, powerful immersion. One centrifugal and the other centrifugal, and both are necessary; They are my two loves. Vagabonding is something I love to do. Call it ‘rag-picking’, looking at ideas and projects that continue to inspire me. At the moment, the various stacks of papers in my library are for a late autumn show with Sally Mann, an American photographer in New York City; a show in Dresden on the monuments; and a book on hymns in poetry form [songs of exile] Through which I hope to understand my complicated half-Jewish, half-Christian upbringing.

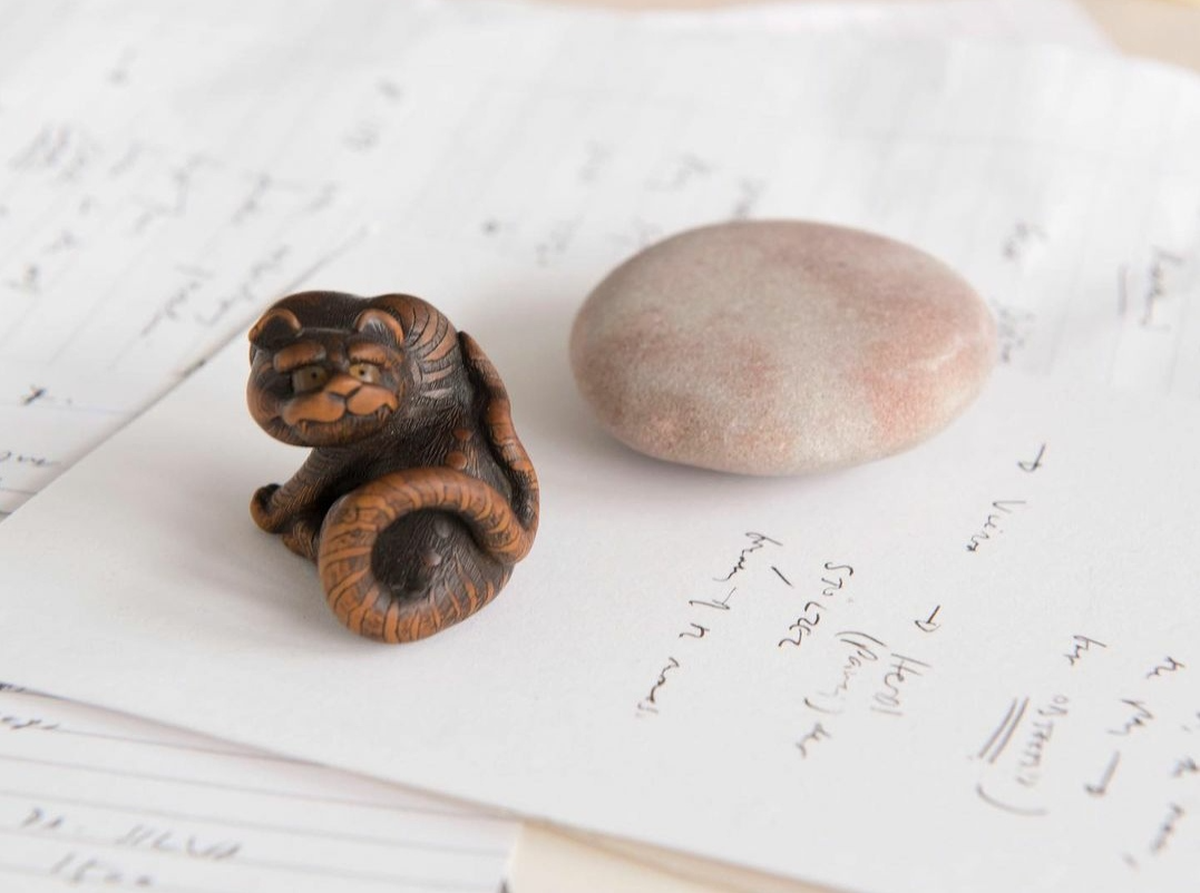

in de Waal’s studio

, Photo Credit: @edmunddewaal

Netsuke donated by the de Waal family to the Jewish Museum in Vienna

What have books done for you?

I feel very insecure. Following in the footsteps of these people has made me feel even more painful about being a refugee and being an outcast. I had done it library of exile Three years ago at the Venice Biennale in honor of my great-grandfather’s library looted by the Nazis in Vienna. It houses a library of over 2,000 books in various languages written by those forced into exile. With an Ex-Libris plate where people can claim this is their story. The exhibit traveled to Dresden, the British Museum, and has now been donated to Mosul, Iraq, where his library was bombed. This is a traveling library. There are communities even in one’s own country where one feels outcast.

We have this extraordinary breakdown. In the end, we are all fragmented, multiple personalities who can love in more than two places at once. This is my true legacy.

The author is a cultural activist, philanthropist and founder of Prakriti Foundation.