Refugee families and independent groups are cherishing the memories of Partition in 1947 with priceless items brought in from across the India-Pakistan border.

Refugee families and independent groups are cherishing the memories of Partition in 1947 with priceless items brought in from across the India-Pakistan border.

My first memory of the Partition of 1947 is a borrowed one, of a James Hinks and Son oil lamp, sitting next to a frameless, monochromatic photograph of my grandfather (dated September 3, 1933), on which Thacker & Co. , Karachi is engraved. my grandmother, or bijik As we used to call her, always starting her split story with the missing handle of Deepak, which accidentally broke on the day she left Karachi with her husband and five-year-old daughter. She was six months pregnant then.

When my grandfather’s friend and Royal Air Force colleague warned her about the possibility of riots erupting in Karachi, she went on to elaborate how she quickly packed all her belongings in a trunk and took Deepak with him. Went. “It was a timely escape. The situation in Karachi worsened after we left,” she blessed and thanked the Muslim man who protected her along with two Sikh and Hindu families during their visit to the port.

The lamp was a symbol of hope and resilience, but not division. “Wealth can be rebuilt, but the dead cannot be brought back,” she said while talking about her lost loved ones.

The remains of the largest migration in the history of mankind – from jewellery, flowerpots and clocks to furniture, letters and utensils – are the weight of 15 million refugees who survived the chaos and segregation. These objects are now being documented by the Punjab Digital Library (PDL), the Partition Museum in Amritsar and the Digital Museum of Material Memory (MMM).

Public Archives: real photo

PDL has digitized over 17,600 letters and postcards sent to officials of the East Punjab Liaison Agency. Laxman Singh of Nankana Sahib, in a letter pleading for help from Wazir Sahib of Gurdwara Sri Dukhniwaran Sahib, Patiala, said that 400-500 villages of Lyallpur have been surrounded by mob.

A photograph of the letter sent by PDL to the digitized Bashambar sweeper

i will be here in lahore

A photograph of the couple, along with a letter sent to the chief liaison officer, was a rare find by the Punjab Digital Library. In a letter dated 28 May 1948, Bashambar Sweeper’s wife requested the authorities to evacuate him from Lahore, Pakistan.

He replied in Urdu: “We have read our lady’s letter and have decided that I want to live in Pakistan with my own pleasure. Mashroki, I don’t want to go to Punjab. (After reading my wife’s letter, I have decided to stay in Pakistan. I will not go to the divided Punjab).’

His statement along with the photograph was sent to his wife on July 29, 1948, through the East Punjab Liaison Agency.

Letters and postcards sent for the search and evacuation of different brothers, mothers, fathers, sisters and daughters are another heavy part of the liaison agency’s records.

“It took seven years to digitize these records from the Punjab State Archive Department. No one has accessed these records before,” says Davinder. “To tell our stories, we must preserve tangible memory. Technology cannot preserve deep memory. It is only through these objects that it can be transferred to the next generations. The way we remember is Decides the way we react. Physical objects are one of the best ways to transfer memories to the next generation,” he adds.

Davinder’s family also witnessed the split. Her mother Manmohan Kaur, 75, still has a phulkari, a glass and a bronze tray that her mother brought with her from Pakistan, while her father Jasbir Singh, 84, keeps his father’s pocket watch. “Waiting for a train to Amritsar at Silanwali railway station in September 1947, my father anxiously glanced at his watch again and again. It was that hour,” says Jasbir. They remember the violence of Partition like yesterday. “This watch was the only thing we got along with, everything else was either lost, robbed or locked in a house we never returned,” he says.

Davinder Singh of PDL with phulkaris and utensils brought by his parents during Partition; Photo: Sandeep Sahdev

Personal Stories: Knowing the Past

“An object has the ability to hold on to history, layer by layer, generation after generation, and eventually – as each generation creates new memories with the objects – becomes a palimpsest for family stories. Material, age, wear and tear can speak to the time it has seen and, in that sense, act as a portal into history – familial, physical, social, even political, “the zenith.” says Malhotra, who has written three books on Partition and co-founded the Museum of Material Memory with Navadha Malhotra.

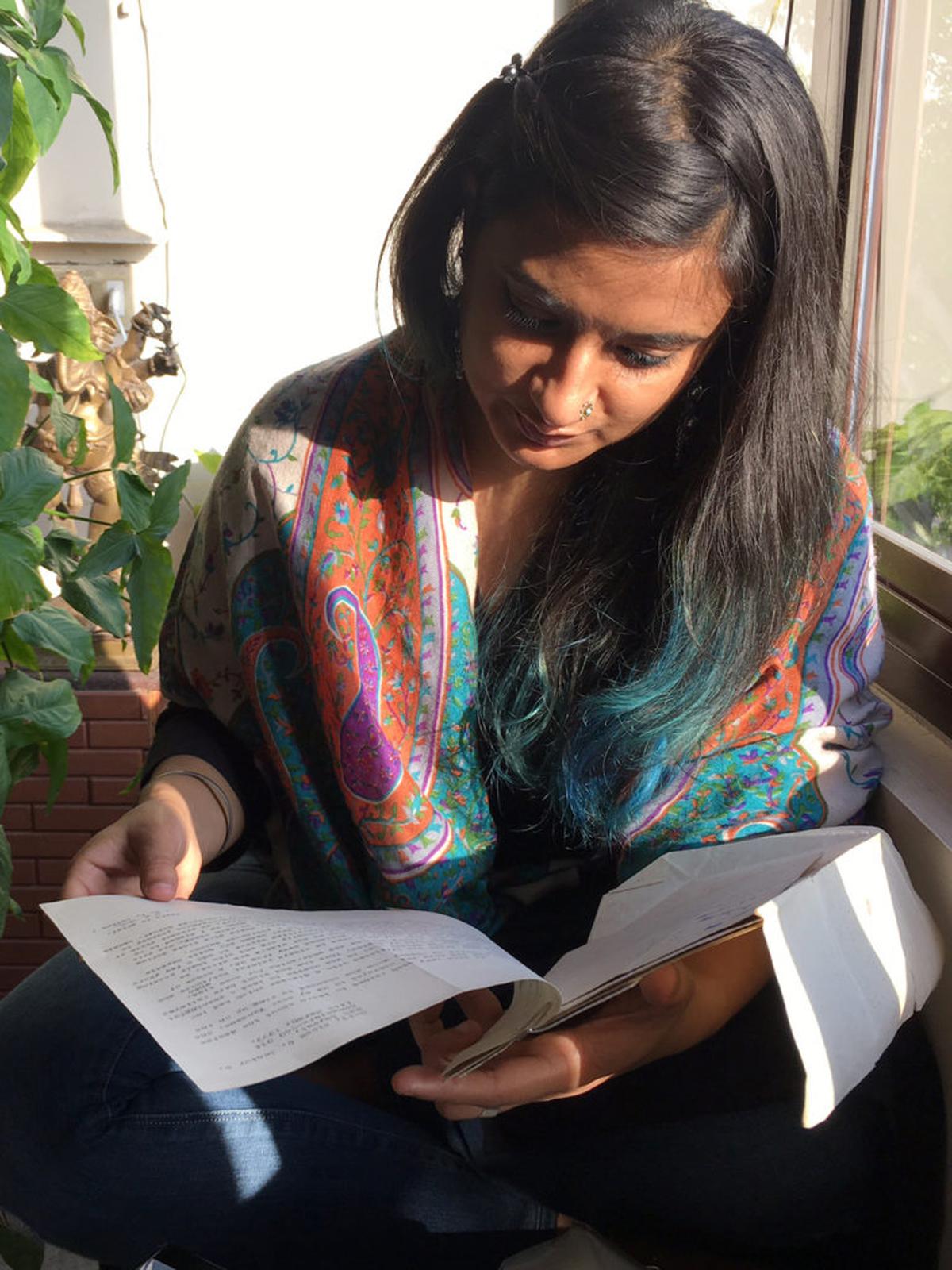

Navadha Malhotra scrutinizes her grandfather’s documents; Photo: Special Arrangements

The museum is a crowded digital repository that traces family history and social ethnography through heritage, collectibles and antiquities from the subcontinent. “In the beginning, we wrote many of the first stories ourselves. For example, Navadha wrote about a gray briefcase that belonged to her grandfather, and I wrote about silver coins that belonged to my grandmother,” says Aanchal.

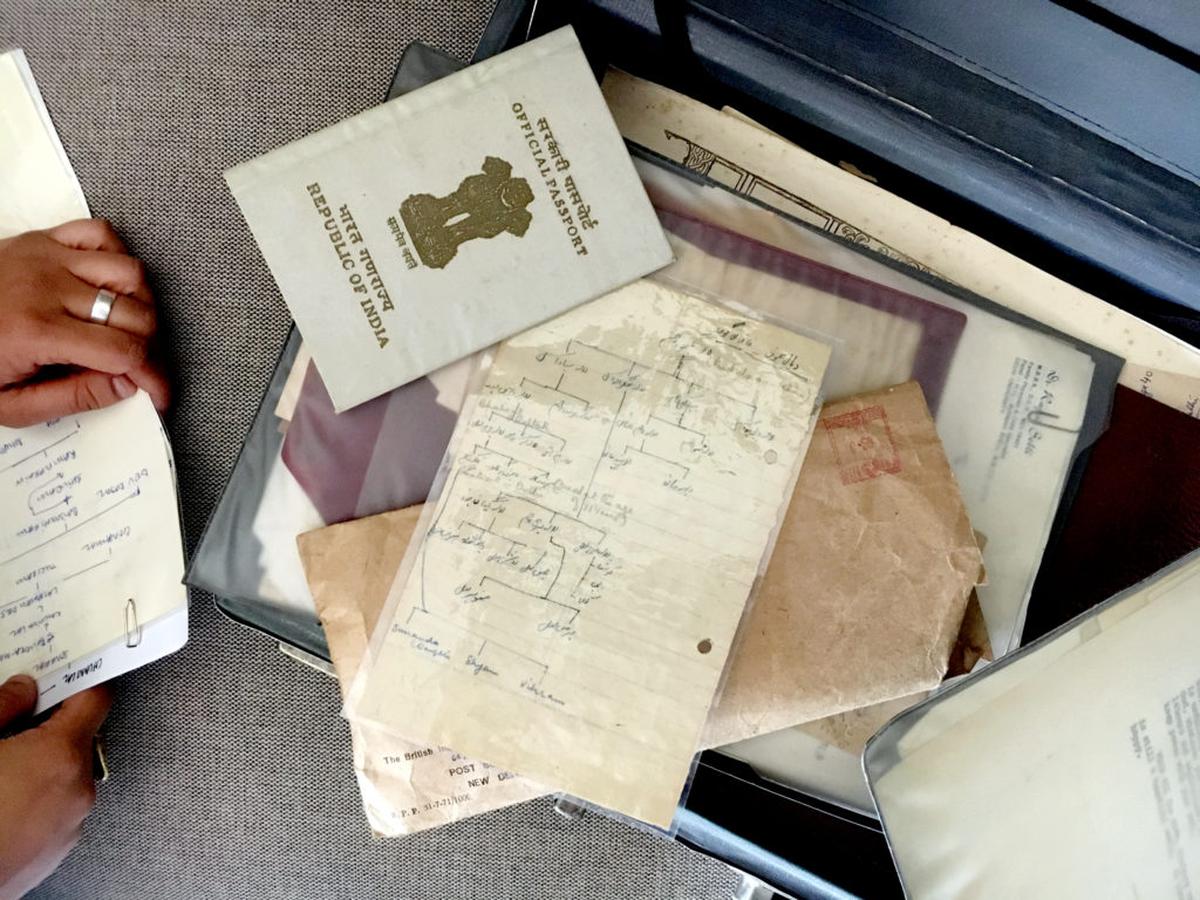

Navadha found her family tree in her grandfather’s briefcase, which also contained his passport, education certificate, receipts, pension documents and a political victim certificate issued by the Government of India. “My grandfather had Parkinson’s disease; I don’t remember ever being able to understand what he said, because by the time I was older, the disease had gotten worse,” she wrote in her account.

The contents of the briefcase of Navadha’s grandfather; Photo: Special Arrangements

silver seaOriginally published in Aanchal’s Book Remnants of a Separation: The History of Partition Through Physical Memory, is the story of how her memory connects with her grandmother’s experiences through a pile of one-rupee silver coins. Aanchal’s grandfather had passed away a few weeks earlier and this was the first time he had seen his grandmother’s collection of coins (1904–1947).

Aanchal scrutinizes old documents with her grandmother; Photo: Special Arrangements

While most museums highlight materiality and objects in historical context, Aanchal feels they rarely provide a personal lens to the original owner and the memories that have been preserved within.

visual history

The Partition Museum in Amritsar houses over 70 items donated by refugees. The oral history of objects creates a parallel relationship with the object and its owner.

Partition Museum in Amritsar

Kishwar Desai, chairperson of The Arts and Cultural Heritage Trust, says, “We have been collecting oral histories and objects for over seven years; It is a slow and steady process. The meeting with the donors happened six years ago, when we were collecting materials. One oral history will lead to another, and one donor to another survivor.”

She explains that a new partition museum to be built in Delhi at the Dara Shikoh library will have a new collection, different from the one in Amritsar. Existing objects on display in the museum include PhulkariHoldalls, trunks, a sewing machine, letters by Justice Teja Singh to his sons, a photograph of a woman with her one-year-old daughter who was lost during the Partition, and even a briefcase.

Kishwar Desai at the Partition Museum in Amritsar | photo Credit:

Kishwar says that since it was a physical museum, it was felt that they could also collect physical memory while collecting oral histories. “It has become a powerful memory of the time as the donated material was a testament to the cultural and social life of the people. For example, a letter written to family members when violence was imminent, a piece of cloth for a wedding.” The piece that had been shelved, a precious sewing machine that would be used to rehabilitate the survivors, or a utensil needed for cooking in both the camp and the last remains of the house, were added to reality.”

history lost and found

Sunaini shows the album which contains the picture of her grandfather with Balraj Sahni; Photo: Sandeep Sahdev | photo credit: Sandeep Sahdev

The everyday objects brought in by the refugees speak volumes about how the Partition was carried out. Most people left Pakistan thinking that they would return, but only a few did. Punjabi singer Surinder Kaur came to his house in Lahore in 1999, says his daughter Dolly Guleria. “In 1997, in Pittsburgh, USA, an old couple gifted me a small album. It had pictures of a house where ‘mama’ lived before partition. The couple said that they moved into the house after the split. When Mama saw the album, she became uncontrollable. The album is wrong now,” she says. His daughter, Sunaini Sharma (52) shared that she still has an album of her grandfather with a picture of her with Balraj Sahni. “It dates from the early 1920s, during his college days in Lahore,” she says.

photo of Sunaini’s grandfather (front row, second from right) with Balraj Sahni (front row, second from left); Photo: Sandeep Sahdev | photo credit: Sandeep Sahdev

Hockey legend Kabir Singh, grandson of the late Balbir Singh Sr., says his grandmother brought the three-time Olympic champion’s first national championship medal from Pakistan when she brought him to the Indian side from her home in Lahore’s Model Town. . of Punjab.

“He presented it before their wedding (during their courtship) and he wore it around his neck constantly. In 1985, this medal and 35 other international and national medals were presented by Grandfather SAI (Sports Authority of India) for their so far sports museum project, but these have been lost along with everything related to them, including their captain’s blazer from 1956 and over 130 original photos,” he shares .

For Kabir, the medals are memories of his grandfather’s time leading up to Partition, a reason why he hasn’t exhausted his quest to get back his memories even after 37 years. “It is not objects, it is the memories attached to them; they are priceless,” he says.