As monsoons shake the land, weeds and weeds are thriving. Meet the People Who Can Help You Identify What You Can Add to Your Next Sunday Lunch Menu

As monsoons shake the land, weeds and weeds are thriving. Meet the People Who Can Help You Identify What You Can Add to Your Next Sunday Lunch Menu

Fodder making is not a new concept. Indigenous communities around the world have always collected wild plants, berries, and other foods. For example, in Odisha, among the Kondh community, a typical meal would consist of grains, such as wild onions, mushrooms and greens. Gondi Saag, all extracted from the surrounding forests. In Meghalaya, the Khasi community collects wild mushrooms and edible greens (such as Jatira And Zamirdoh) for their food and to sell in the local market.

Fruits for a walk among the Sahyadris in the North Konkan Western Ghats. photo credit: Sanjeev Valsan

We’re no strangers to it, cities – I remember picking up ripe Jamun who had fallen from the trees in Delhi, and the flakes of Kalmi greens or water spinach, and kochu address Or colocasia growing around water bodies in Kolkata.) Over the years, an increasing number of people are adopting urban pasture. You will find forging walks in almost every metro city of India. While some gather produce, others use walking trails to connect the younger generation to traditional food systems.

Monsoon is a great time to forage, and what people eat and eat during this season varies across India. “In Bengal, for example, people avoid eating greens, but in Tamil Nadugreens like amaranth or gotu kola [centella asiatica, with detoxing properties] is consumed,” says Nina Sengupta, an ecologist from Auroville who conducts on weekends edible weeds. But all expert foresters agree that doing it right takes time, patience, and a lot of training—because you can confuse something poisonous with something edible. We speak to four villagers who are helping people to ‘eat the wild’.

Savita Uday | photo credit: Buda Folklore

Savita Uday

Founder, Buda Folklore

Come monsoon, in August, you’ll find hordes of urban school children in the middle of the Angadibel forest in Uttara Kannada (North Karnataka), participating in mungaroo programs celebrating the rain. Foraging walks will be a big part of the “Mungaru forest has a lot to offer”, explains Uday, who started the organization in 2006 to preserve the rich biodiversity and folk tales of the indigenous people of Uttara Kannada.

forage edible wild plants | photo credit: Buda Folklore

“For example, we feed Kusumle Hanua wild flower tent [a digestif drink], Jamun tastes like apple. there also Moore shrugged, A wild fruit, used as a . is done as urad dal substitute for dosa, When it is ground into a paste, it resembles the mucilaginous structure of ground black gram.

Each season has its own variety of foods. In winter, they forage for tubers and roots, and in summer, for wild fruits and berries. “Nature has already made a food chart for us to follow,” she says, during the monsoon. soppu (tender leaves) are plentiful. “We once held a wild colocasia leaves festival in the village, where we documented more than 10 varieties, including one that grew on trees. They are rare and grow on older trees, so you’ll have to climb the bait. we made the best custodian With these leaves.”

They also have ‘Live and Learn’ programs where every meal is cooked with the ingredients of the feed. budafolklore.in

Shruti Tharayil | photo credit: Forgotten Greens

Shruti Tharayil

Founder, Forgotten Greens

Tharayil became interested in wild, edible plants while documenting the work of Aboriginal peasant woman Telangana in 2011. She noticed that they had used wild greens which she had always believed to be poisonous. Her interest led her to research it – talking to people, and reading books. Back in 2018, KozhikodeIn Kerala, he started Forgotten Greens to create awareness about edible but ‘lost’ plants that were once a part of our diet. except today KeralaTharayil has hosted workshops on wild foods in places like Udaipur and Chennai. She also conducts an online workshop called Rewild Your Life, where she shares information and recipes about a plant every day.

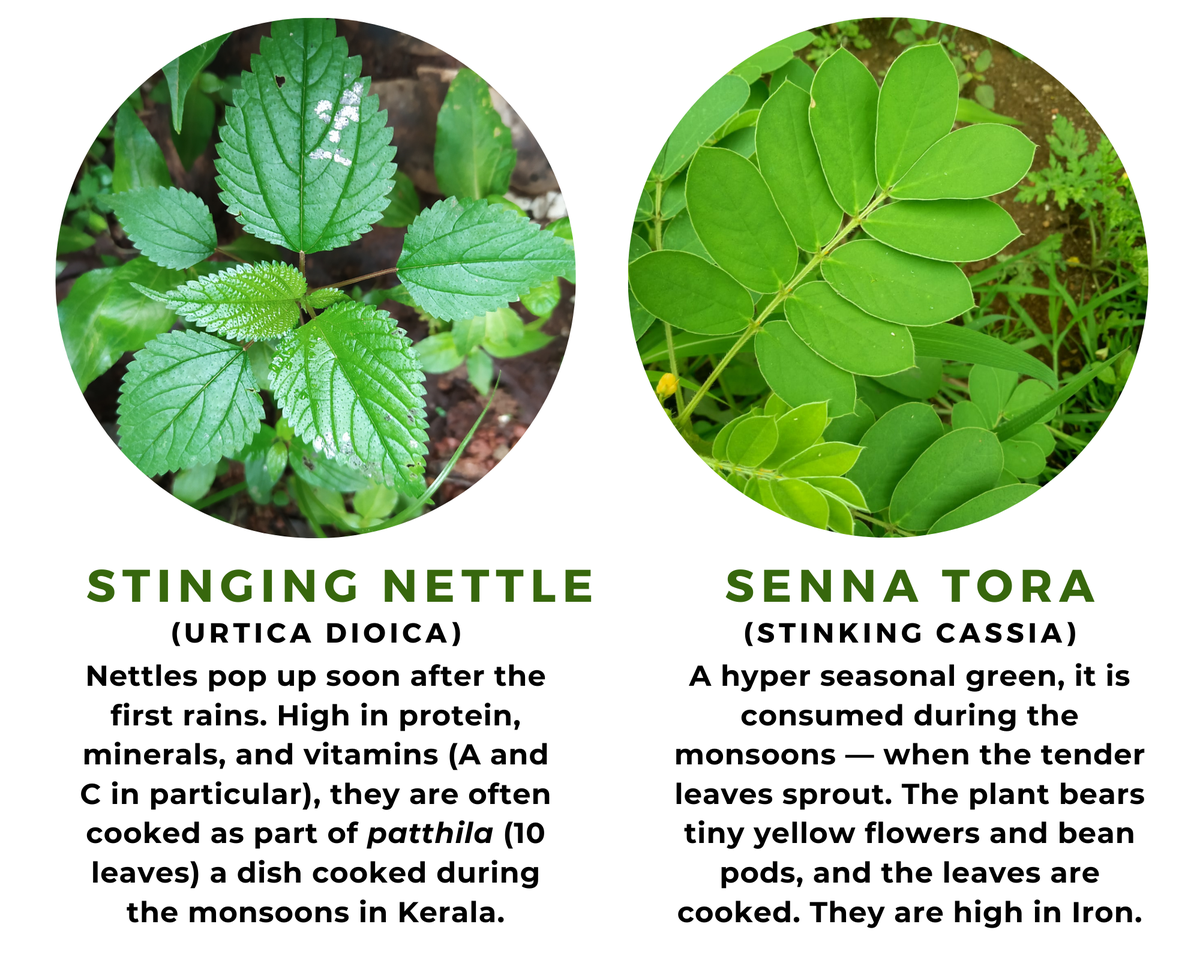

Among the wild foods Tharayil has documented are stinging nettles that sprout soon after the first rain. “High in Protein, Minerals, and Vitamins” [A and C in particular]Nettles were traditionally a part of our diet,” she says. “The leaves are often used in” rocky, which is cooked during monsoon or karkidakam masami [when the community consumes different kinds of medicinal herbs]Pathila pylon, which literally translates to ‘ten leaves’, is cooked with a garnish of forest greens and coconut. “The recipe varies according to knowledge of the greens and pasture available in the backyard,” she says.

@forgottengreens on Instagram

Neena Sengupta | photo credit: Tripti Kedar

Neena Sengupta

Ecologist. Host Food Weed Walk

Sengupta travels the world as an independent consultant integrating biodiversity conservation and sustainable development options. She organizes Edible Weed Walks, hosts a podcast, and runs Edible Weed Walks, a YouTube channel where she gives useful tips on urban foraging. (She advises beginners to visit vegetable markets in their cities “where you will often find elderly women selling wild greens which they forage for themselves”.)

Sengupta believes that people should not look at pasture in isolation. “People tend to think in flat terms like this: is it edible/medicinal, is a plant/weed useful? These are words of disconnect. People don’t ask what a plant is? I try to explain it All – edible, inedible – is a community, an ecosystem. The plants/weeds you need are dependent on the ones you want to ‘weed’ for their survival.”

She says walking can help bridge the disconnection from the ground. “Right now, I’m wearing a pair of trousers that are naturally printed with leaves,” she tells me. “The woman who took a walk with me made it a whole new approach to her venture. She now uses leaves for natural prints. I love that. It shows that you are integral to your surroundings.” Huh.”

Monsoon brings with it greens like amaranth (with cooling properties) and red pea brinjal (Solanum trilobatum). “Stem and Leaves” [of the latter] There are thorns, but when you cook the leaves, the thorns melt away. is added to rasam or built in Bhajji,” she says, adding that people in Tamil Nadu eat cool and bitter green vegetables during the rains. to like gongura Or Roselle, whose fresh leaves are now available.

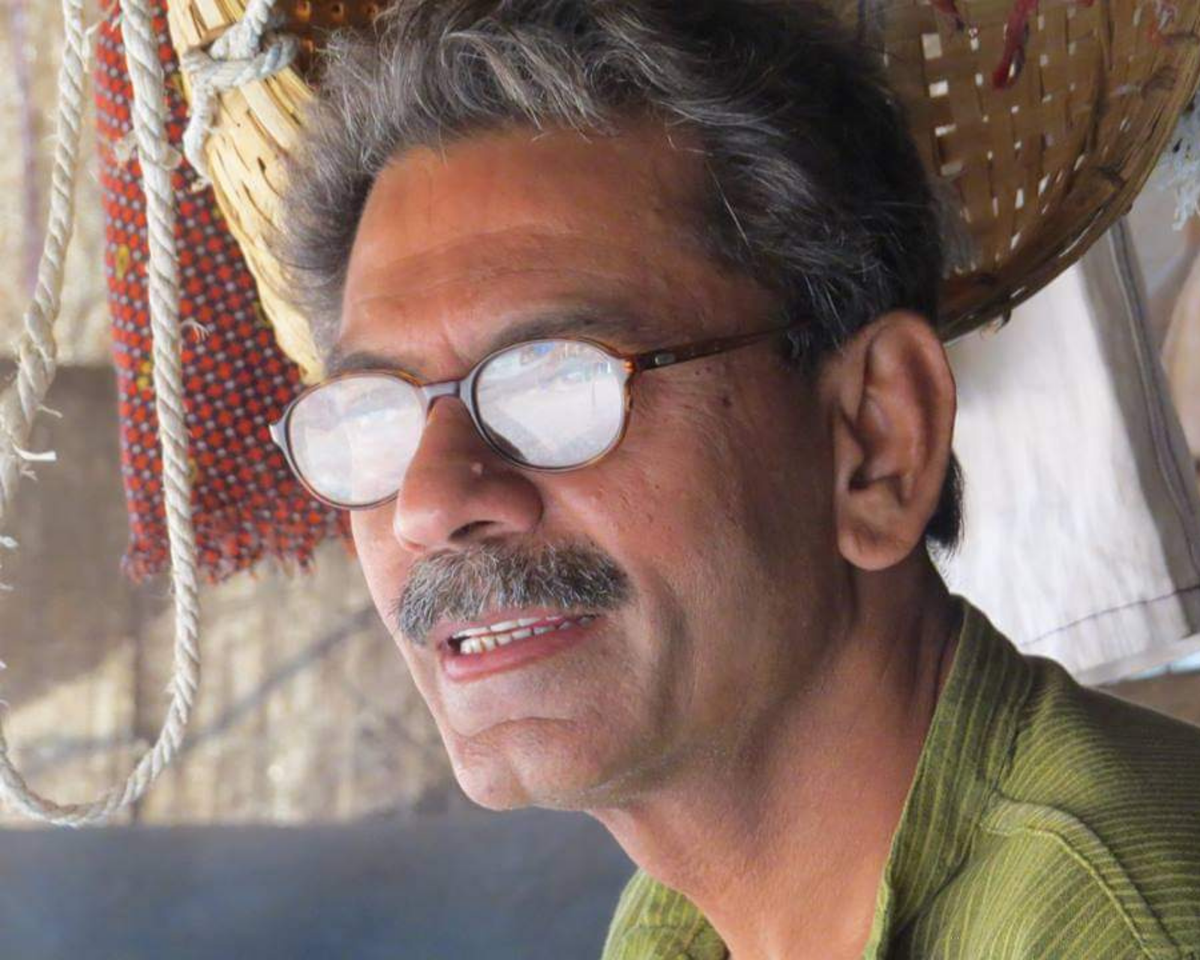

Mr. Suresh Kumar photo credit: Sarjapur Curry

Mr. Suresh Kumar

Founder, Sarjapur Kariz

Exploring wild foods can mean discovering fresh or forgotten flavors – artist Suresh Kumar has fond memories of dishes his mother and aunt cooked with edible weeds. Art College (New Delhi) alumni started Sarjapur Curry in 2019 as a community garden to revive edible weeds and local greens through urban gardeners’ workshops, walks and meet-ups. The project has helped village communities to revive more than 15 types of edible weeds and more than six types of wild plants such as kuppakku And komekku, They have also established a seed bank that preserves about 25 different types of edible weeds, including come akku (hogweed), gonakku (regular pursuit), and pulsakku (Oxalis).

Suresh Kumar leading the tour | photo credit: Sarjapur Curry

The idea is not just to bring back plants, but also to bring back old and lost recipes that use them. For example, with the monsoon season, the trend would be Anne Soppu (water spinach) growing wild. People make a simple stir-fry with it or add it to lentils. bassru (One team and greens dish). , bassru either bus saru a very popular gravy recipe from karnataka, which is served with ragiissues [ragi balls] Or rice in Bangalore, Mysore, Mandya, Hassan, Tumkur and Kolar regions of Karnataka.”

@sarjapura_curries on Instagram

India mind

Co-Founder, Forester

The Vanavadis, a forest group in the foothills of the Sahyadris in the northern Konkan Western Ghats, have been hosting forest pastures almost every year since 2012. These usually occur during the last weekend of June or the first weekend of July – in the form of early monsoons. This is when they have maximum availability of wild, uncultivated food items. The walks (about two hours each) are usually manned by the elderly. Aboriginal women of the area. A translator (English/Hindi) is provided for those who do not read Marathi. Meals include foods collected during a walk.

Vanwadi tour is usually done by elders Aboriginal women of the region. photo credit: Sanjeev Valsan

“In Vanwari, a primary inventory yielded more than 120 forest species known for various traditional uses. In addition to edible species, we found that we had more than 45 species with known medicinal uses and at least 20 wood species. Then there are plants that produce natural colours, edible oils, gums and resins, botanical pesticides, etc., in addition to fodder, bio-fuels, hedge protection and craft materials. Many species have many uses. For example, the leaves of Mahua The trees provide fodder, the flowers are used to make molasses, wine or porridge, and the fruits are eaten or cooked as a vegetable. Oil is extracted by crushing the seeds [The residue is valuable manure for farm crops]”says Mansta. “During the rains, we gather” Shevla [dragon stalk yam], cartula [spiny gourd]and berries like caravanda [black currants],

vanvadi.org