Form of words:

New Delhi: More and more poor households in India now have access to institutional sources of credit, reveals the latest round of All India Credit and Investment Survey (2019) Issued by Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation earlier this month.

The data shows that over the years, this increased institutional credit has led to a reduction in usury, a common practice in rural India, in which loans from poor households are charged exorbitant interest rates from traditional moneylenders.

According to the survey, in 2018, institutional credit accounted for around 66 per cent of the total outstanding credit in rural areas, the highest since independence.

In stark contrast, almost five decades ago in 1971, barely 29 percent of households in rural India had institutional credit available.

However, the survey noted that the change has not been uniform everywhere. In some states, non-institutional creditors still dominate the lending business, but there, too, the trend is downward.

As of June 30, 2018, non-institutional financiers, mostly professional moneylenders and relatives, accounted for about 34 per cent of total credit in rural India, the survey said.

But in states like Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Bihar, they still account for more than 50 per cent of the total outstanding loans. Even in Jharkhand (40.6 per cent), Odisha (40.8 per cent), Rajasthan (46.6 per cent), Uttar Pradesh (37.2 per cent) and Madhya Pradesh (34.4 per cent), non-institutional credit was slightly higher than the national level. An average of 34 percent in rural areas.

But the share of non-institutional credit in rural areas is falling in all these states except Andhra Pradesh and Telangana.

According to the survey, Bihar saw the sharpest decline in non-institutional rural credit, from around 78 per cent in 2012 to 51.5 per cent in 2018.

In Rajasthan, the share of non-institutional agencies in total rural credit fell from 69 per cent to 47 per cent in the same period. The decline in this regard was relatively slow in Odisha (43 per cent to 41 per cent) and Uttar Pradesh (43 per cent to 37 per cent).

moneylenders are losing

Data shows that between 2012 and 2018, professional moneylenders lost out to commercial banks.

In 2012, traditional moneylenders and agricultural creditors accounted for 33 per cent of the total rural credit. In 2018, their share has come down to just 22 per cent. This figure includes lending by both professional and agricultural lenders.

traditional moneylender or moneylender have been present in Indian villages for centuries. These lenders charge a high amount of interest which often puts the debtor in a debt trap.

According to All India Rural Credit Survey driven By the Reserve Bank of India in 1951, these moneylenders accounted for about 70 per cent of the total rural credit at that time.

Only the convenience and availability of little or no collateral made these lenders accessible to the poorest households in rural India and they faced no competition from organized banking decades after India’s independence.

Till 1971, non-institutional loans Responsible Rural India accounted for over 70 percent of credit, which fell to 38 percent by 1981 as the effects of the 1969 bank nationalization began to show results, with bank branches spread across the country.

The credit survey states that credit by scheduled commercial banks, which in 1951 was not even a percentage of rural India’s credit, has registered a huge jump. As of 2018, about 42 per cent of rural India’s credit was channeled through these banks, up from 25 per cent in 2012.

According to Narayan Chandra Pradhan, Assistant Adviser in the Reserve Bank of India,”Rural finance is gaining momentum after the Jan Dhan Yojana of 2014, but the real helpers are non-banking financial corporations (NBFCs), small finance banks and cooperatives through the mobile banking system.

While public sector banks, since nationalisation, have been at the fore in providing credit to rural areas, private banks have played their part, in part thanks to increased financial literacy.

Over time, since people started getting subsidies directly into their accounts, transparency in transactions has brought millions of account holders to paper.

India’s leading private sector bank, HDFC currently has 1 lakh branches in villages, with plans to expand to 2 lakh villages by 2023, Rahul Shukla, Group Head (Commercial and Rural Banking) of the bank said et now.

Shukla also said that if the banks want their business to grow continuously, then they will have to move to the hinterland.

A senior official of the private bank, on the condition of anonymity, told ThePrint that “the banks may not open their own branches, but they keep sending their agents to the villages.”

“Direct transfer of sale proceeds to the bank accounts of farmers, increased use of ATM cards have put their financial transactions on record, thereby reducing the barriers faced by farmers in getting bank loans,” the official said. Is.” “Competition is increasing, with more and more private banks trying to exploit this market.”

ThePrint reached SBI The group’s chief economic adviser, Soumya Kanti Ghosh, reached for a comment via email but did not receive a response till the time of publishing this report.

Who benefited the most?

The decline of traditional moneylenders has actually benefited the lowest strata of the economy.

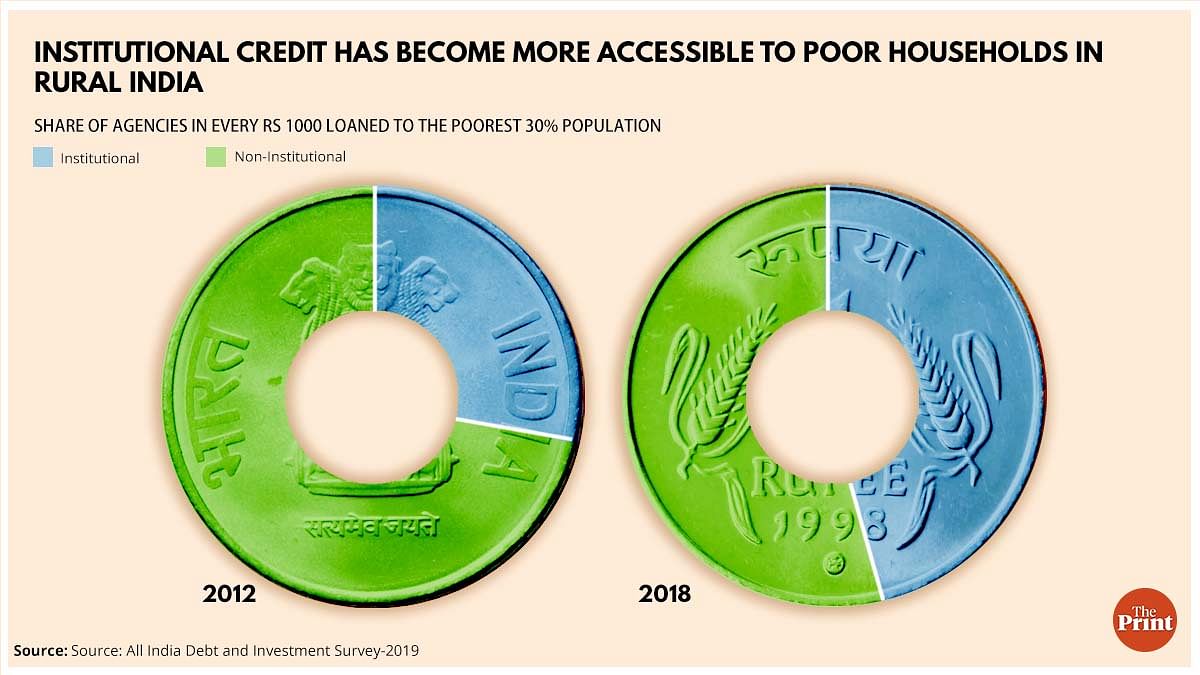

The data shows that the transition from professional moneylenders to commercial banks was highest in the bottom 30 percent of asset-holder classes (or the poorest 30 percent).

In June 2012, according to the survey, for every Rs 1,000 loaned to the poorest 30 per cent, more than Rs 500 came from moneylenders alone. This figure has been halved in 2019 as they were the source of credit of only Rs 277 for every rupee. 1000 loaned to this particular demographic.

This is mainly because institutional sources of credit have become more accessible in these areas, the survey said. In 2018, for every Rs 1,000 given to the poorest 30 per cent, more than Rs 453 came from institutional sources, a nearly 60 per cent jump from Rs 286 in 2012.

This growth was mainly led by scheduled commercial banks, whose share in total credit to poor rural households nearly doubled between 2012 and 2018. In 2012, the share of scheduled commercial banks was about Rs 107 for every Rs 1,000 given to rural India. Reached 233 by 2018.

According to JNU professor Praveen Jha, this is a “welcome change”. However, he added that it still needs to be examined in relation to the agrarian distress that has arisen over time.

“We need to inspect new sources of institutional finance. If people are pledging gold for bank loans, it will be reflected in institutional credit, but it does not reflect a crisis in the economy,” he told ThePrint.

Jha said, “Increased institutional credit to the poorest households may offset the loss of interest rates charged by moneylenders, but we have to acknowledge that the rise in the cost of farming has made agriculture a less profitable occupation. Is.” “This essentially means that the agrarian crisis cannot be completely ruled out, even if the source of credit has improved.”

(Edited by Arun Prashant)

Read also: India’s world-beating GDP data can’t hide the pain of the pandemic

subscribe our channel youtube And Wire

Why is the news media in crisis and how can you fix it?

India needs free, unbiased, non-hyphenated and questionable journalism even more as it is facing many crises.

But the news media itself is in trouble. There have been brutal layoffs and pay-cuts. The best of journalism are shrinking, yielding to raw prime-time spectacle.

ThePrint has the best young journalists, columnists and editors to work for it. Smart and thinking people like you will have to pay a price to maintain this quality of journalism. Whether you live in India or abroad, you can Here.