Form of words:

New Delhi: For decades, the service industry has underpinned India’s growth and unemployment in the world’s second most populous country. The coronavirus pandemic is now calling for an immediate rebalancing of the economy towards manufacturing.

High-contact services jobs from airlines to hotels and malls to multiplexes were among the first to collapse amid prolonged lockdowns aimed at containing the virus. The decline of this sector, which typically accounts for 55% of the economy, is forcing people to work on rural farms or in small-sized manufacturing industry.

55-year-old Ramesh Jakhar is among those hit. He used to drive a bus to Sam’s International School in New Delhi, where he earned 16,000 rupees ($215) a month. Now returning to his village near the capital, he rears buffaloes and sells milk.

“Times are really tough,” said Jakhar, whose unemployed adult son has also returned to his village with his young family. “We’ve been forced to cut back on what we can spend.”

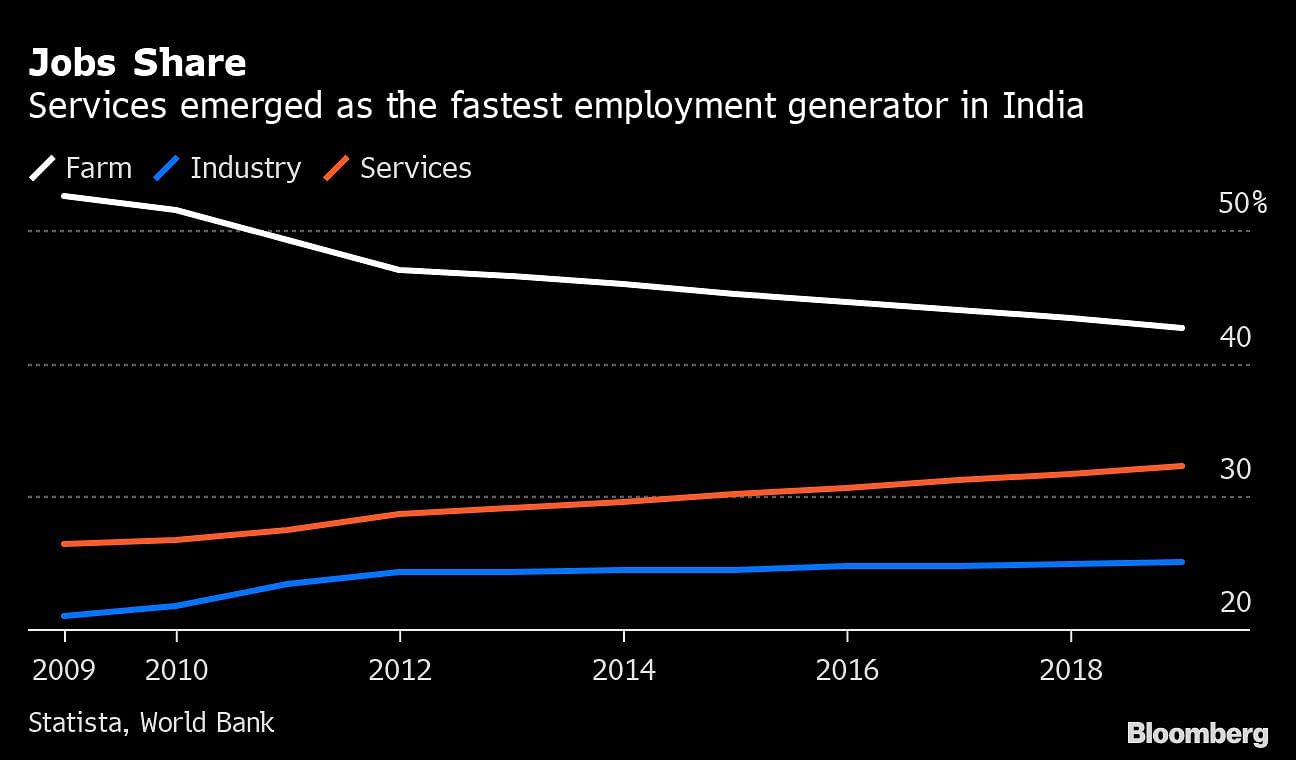

Unlike China, which saw workers move from farms to factories, India transitioned to a service economy – the sector provided more than 32% of total employment by 2020, up from 17% in 1981. At the same time, the percentage of agriculture in the share jobs has fallen from 72% to 42% and manufacturing has fallen to 25%.

“India has jumped from agriculture to services and has so far missed manufacturing,” said Sonal Verma, economist at Nomura Holdings Inc. in Singapore. “It’s a gap we must fix.”

Boosting labor force productivity is key to rapid economic growth for India, which is recovering from an unprecedented contraction brought on by the pandemic. Data due on August 31 will show GDP grew 21% in the April-June quarter compared to a year ago, setting the stage for an expected 9.5% expansion for the full year.

But India has repeatedly failed to grow its manufacturing base despite the demand from a captive market of over 1.3 billion people. Instead it relies on a flood of imports for everything from heavy machinery to toys. Even Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ‘Make in India’ initiative, which aims to boost manufacturing to 25% of the economy, has failed in the absence of supporting infrastructure and ease of doing business .

According to the World Bank, manufacturing has shrunk to about 13% of GDP from a peak of about 18% in 1995.

“There is a need for rebalancing through targeted policy within sectors,” said Arpita Mukherjee, Professor, Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations. “We can incentivize services that have input into manufacturing.”

The situation has accelerated given the grim jobs market. More than a year after the first Covid-19 lockdown, the unemployment rate is still above pre-pandemic levels and most high-contact service establishments, from cinema halls to schools, are closed. With millions of workers in the country’s vast informal sector facing unemployment or wage cuts, families are limiting discretionary spending.

This is bad news for an economy in which private consumption accounts for 60% of the growth. To sustain spending, India needs jobs for its 986 million working-age population, and ensuring productivity will be key to the sustainable recovery of Asia’s third-largest economy from the shock of the pandemic.

“India will suffer somewhat from the medium to long-term mark,” said Sanjay Mathur, chief economist for ASEAN and India at Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd. “Various companies in entertainment and hospitality will not be hiring for some time.”

The impact of the pandemic will be felt for years. According to a report by McKinsey Global Institute, around 18 million people in India will be forced to move to a different occupation by 2030.

To create new jobs, Modi is trying to revamp his Make in India scheme by subsidizing everything from smartphones to specialty steel makers. In addition, he is simplifying tax procedures to woo global investors.

Still, job creation won’t come soon enough for people like Gaurav Kashyap, 31, who earned Rs 50,000 a month driving students to and from school in a hire-purchase van, which they had to surrender. was forced. He now works as a security person in New Delhi.

“I sat at home for the first six months of the pandemic without any work,” Kashyap said. “If schools reopen I look forward to driving again.” –bloomberg

Read also: Why switching from iPhone to Android Galaxy is like getting a taste of the future

subscribe our channel youtube And Wire

Why is the news media in crisis and how can you fix it?

India needs free, unbiased, non-hyphenated and questionable journalism even more as it is facing many crises.

But the news media itself is in trouble. There have been brutal layoffs and pay-cuts. The best of journalism are shrinking, yielding to raw prime-time spectacle.

ThePrint has the best young journalists, columnists and editors to work for it. Smart and thinking people like you will have to pay the price for maintaining this quality of journalism. Whether you live in India or abroad, you can Here.