K.V. Narayanaswamy

| Photo Credit: D. Krishnan

Carnatic music world was and is often about the personalities more than the music. Music may have ushered them into the limelight but with time the artistes became larger than their music. A few bucked this trend. Palghat K. V. Narayanaswamy, whose birth centenary has been fittingly celebrated over the past months, is a prime example. He stayed far behind his music, which took the centre stage. Perhaps deliberately so. We are, therefore, celebrating KVN’s music more than the man.

KVN’s music could be described as a thani vazhi (unique path). Into the mix went robust tutelage from the doyen, Ariyakudi Ramanuja Iyengar, a repertoire that changed with times, weaving of a characteristic emotive flash, shades of Dhanammal school rendition, intelligent but optimum use of laya and the primacy for sowkhyam that almost became his first name. He cleverly took parts of these as they fitted into his conception, rather than blind imitation of what he was exposed to. In a few cases like the overall concert package or the colossal four raga Pallavi (‘Sankarabharananai azhaithodi vaadi kalyani darbarukku’), KVN retained the Ariyakudi prototype. The metamorphosis of his style over his career span came almost unnoticed. The final stage of the product was unrecognisable from the MVP (minimum viable product) that he started off with. Many great musicians struggled to achieve such seamless evolution. This could be attributed to KVN’s pluralistic outlook to all good musical things that came his way.

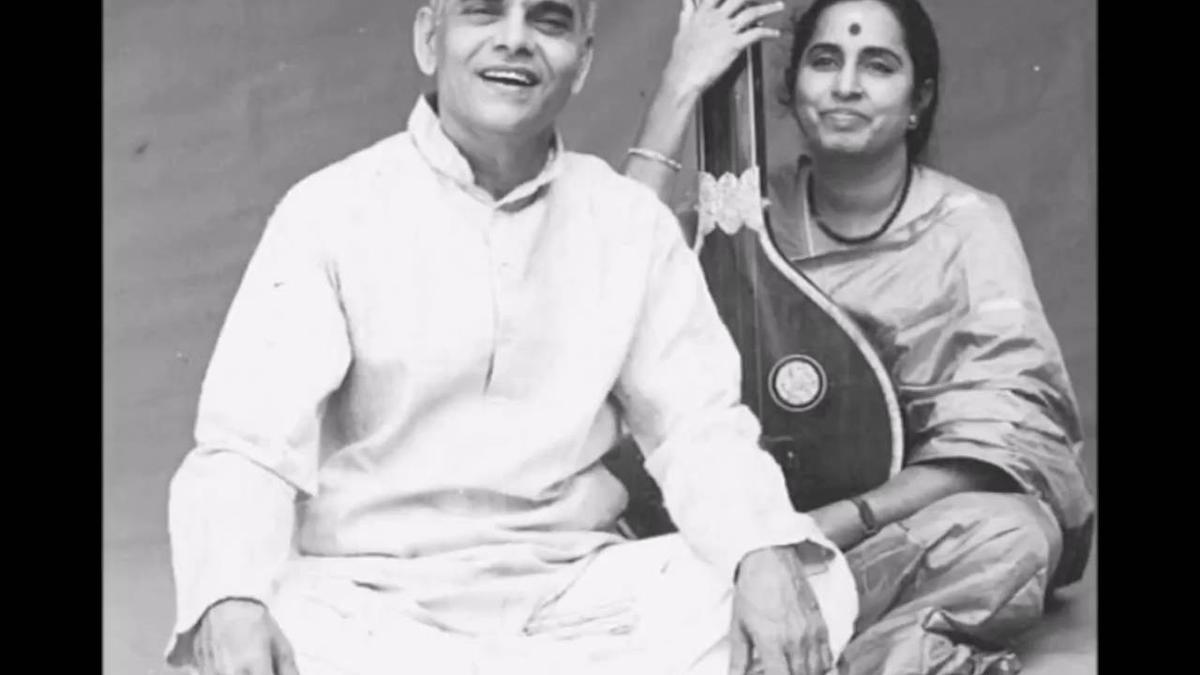

KVN with his wife Padma

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

Melody and sruthi fidelity were non-negotiable for KVN, as was voice subtlety. His silky long-breath voice and range allowed him several liberties with singing a wide repertoire of kritis in all octaves, aligning well to what could have been the composer’s mood — be it a brisk Tyagaraja kriti such as ‘Naradagana lola’ (Atana) or the bard’s evocative ‘Mokshamu galada’ (Saramati) in a stalling tempo or the majesty of an ‘Akshayalingavibho’ (Sankarabharanam, Dikshitar) or the poignant version of ‘Varugalamo’ (Manji, Gopalakrishna Bharati). Bhava was more important than the mechanics of a kriti. The varied tapestry was seen even within a single concert. It was akin to a wholesome meal — nothing too much, nothing too little.

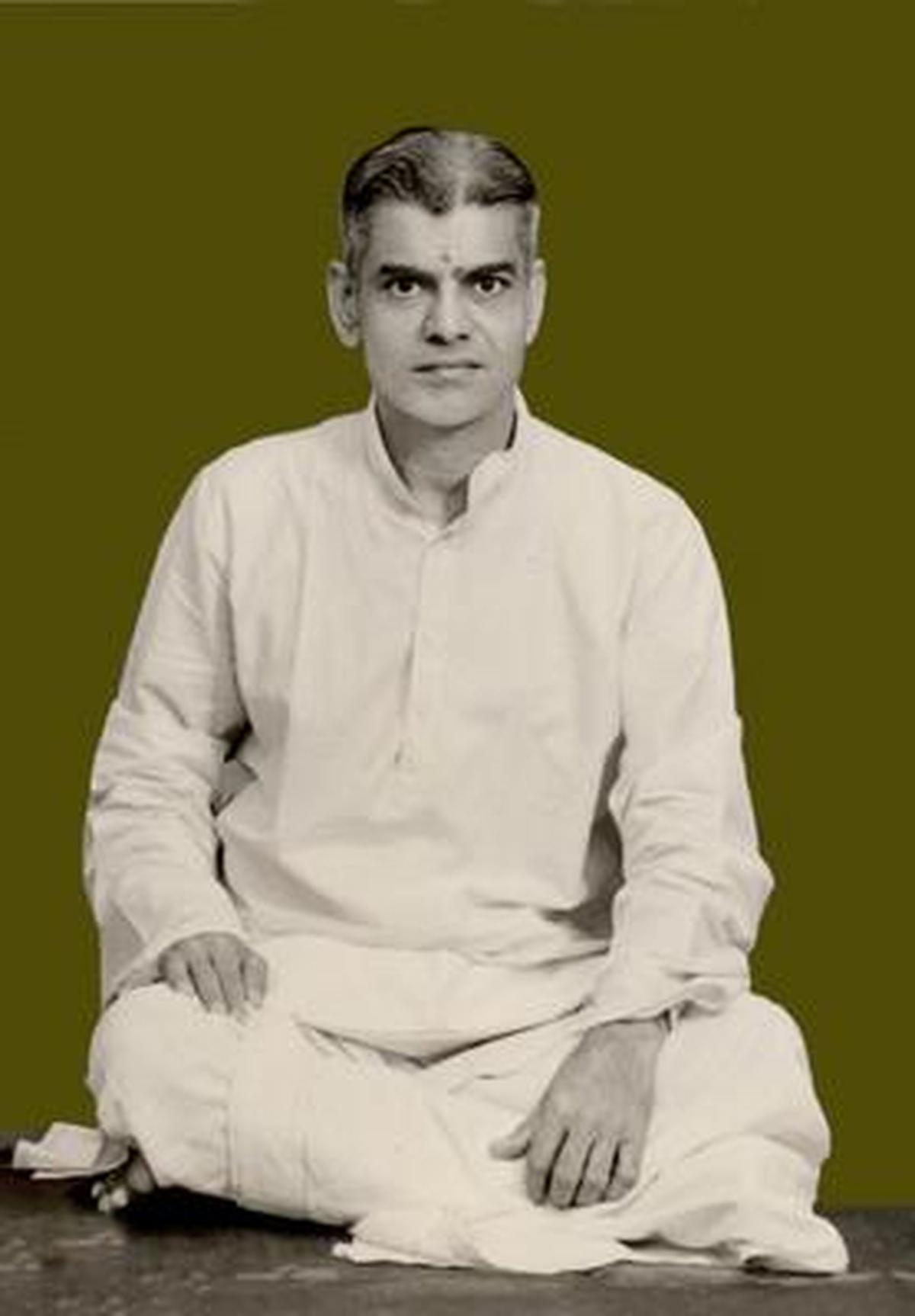

K.V. Narayanaswamy

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

KVN’s manodharama also had some unique grammar — keeping alapanas aesthetic but brief, segmenting sangathis in niraval with laya patterns, swaras that were pleasing but never testing audience’s patience were some elements that KVN never wavered from. In his era, it was par for the course to be excessive, but KVN shunned that approach. He also did not get derailed by stalwart mridangists who could egg the vocalist into a laya combat.

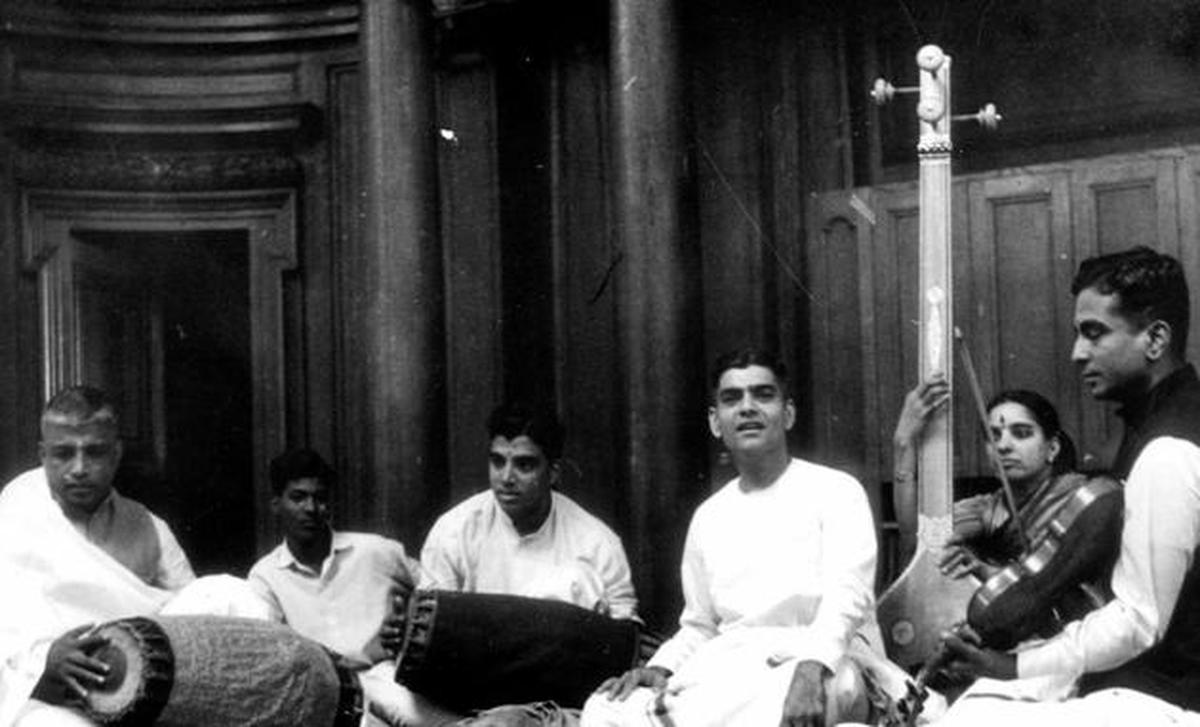

KVN practiced something that may well be a rare virtue. He co-performed with a large array of young and seasoned accompanists. It is quite possible that he never asked for a certain accompanist, thus giving everyone a dignified status. It’s as good a time as any to remember that.

Lalgudi G. Jayaraman (violin) with K.V. Narayanaswamy (centre), T.R. Rajamani (mridangam, left)

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

I am fortunate to hear my mother talk reverently about her training under KVN 70 years ago, when she was a teenager. His teaching principles were also unique. While he would encourage intense practice, he dissuaded his younger disciples from practicing a newly learnt song except in his presence. He cautioned against unintentional etching of a wrong phrase during unsupervised singing (as there was no recording those days).

KVN with D. K. Pattammal

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

Patantara was in the opening page of his dictionary. KVN also suggested that young learners practice in front of a mirror to track and curb their mannerisms. He himself had very little. His left hand was taught to behave! Many competent artistes of the succeeding era went to him to inject his magic into their armoury, just as corporate leaders line up to Harvard University for the Advanced Management programme. KVN extended his teaching contribution to Wesleyan University as well, pollinating the generation that moved out of our shores and Americans with his brand of music.

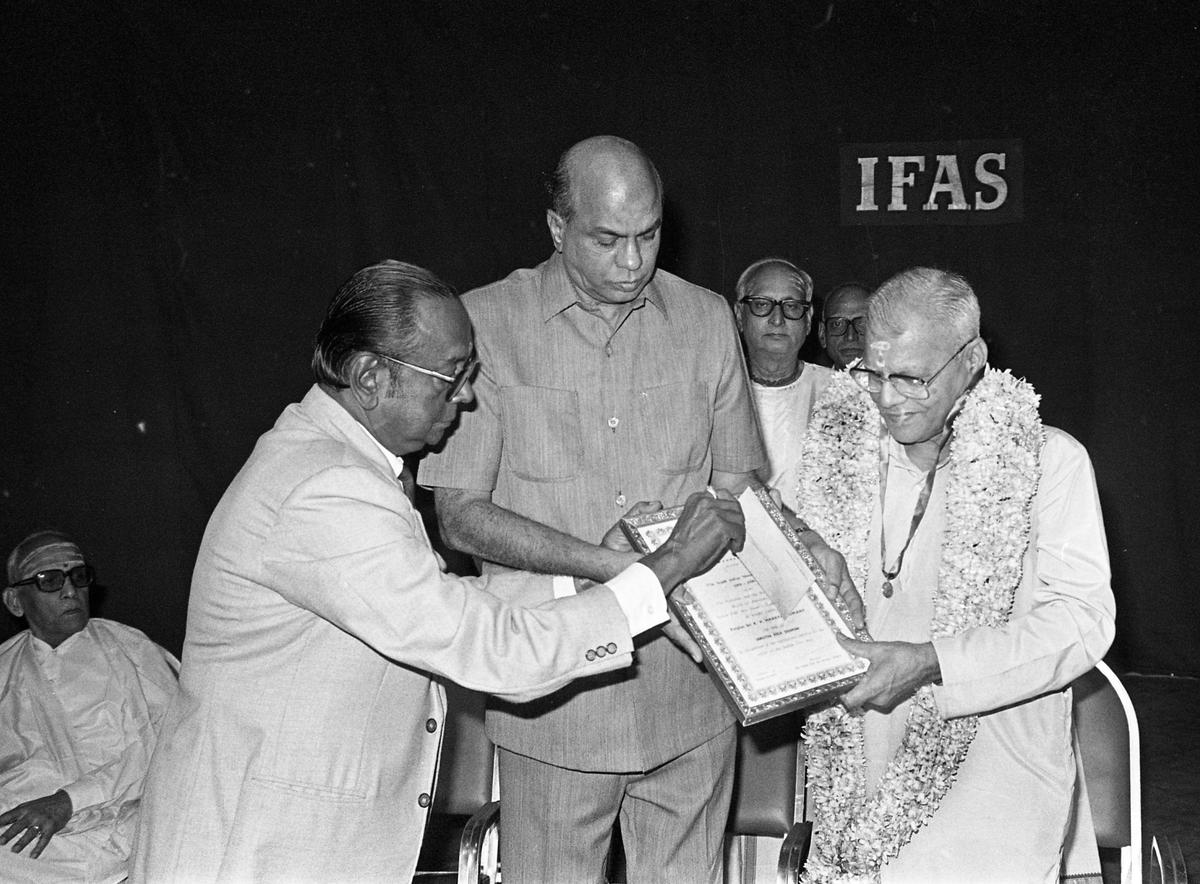

The title ‘Sangitha Kala Sikamani’ being conferred on K.V. Narayanaswami at the 57th Music Conference and Festival organised by the Indian Fine Arts Society, in Madras on December 18, 1989.

| Photo Credit:

THE HINDU ARCHIVES

In later years, KVN embraced compositions of many new vaggeyakaras and made some of them popular. It would have been only because he found the music in such new compositions, profound and authentic. For a man whose musical mastery was comprehensive, KVN spoke little and let his music do the talking. As his health cramped him and his tempo slowed in his later stages, he used the opportunity to enhance his soulfulness even further. It seemed like the message that he wanted to leave behind — that music has to hit the soul, first and always! That’s one principal reason why Carnatic music lives on. And so does KVN’s outstanding legacy.