Form of words:

YouLike many ‘important’ decisions in the past, the Narendra Modi government needs congratulations for releasing “National Monetization Pipeline” Document in two volumes in the public domain. This will bring some clarity to the government’s thinking about mobilizing resources by monetizing critical assets created during several decades of public investment. There is an expectation that the documents will be read carefully not only by the officials of the Ministries and Public Sector Undertakings, whose vital assets are proposed to be given to the private sector for long-term use, but also by their employees and other stakeholders.

Unlike privatization, the ownership of assets will not be handed over to the private party and will later be returned to the government after the monetization period is over. At least this is the theory. While the road, railways and power sectors will offer huge assets for monetization, in this article we examine the monetization proposals for the warehousing sector.

Impact on MSP

Many expert committees It has recommended to reduce the purchase of wheat and rice at the Minimum Support Price (MSP) in the last few years. However, the National Monetization Pipeline (NMP) acknowledges that due to the MSP policy, there is a need to increase the storage capacity. For this it sets four objectives.

First, it recommends improvements to the storage infrastructure. Second, it calls for reducing the cost of storage and operation. Third, it suggests a reduction in losses in the storage and handling of food grains. And finally, it proposes to reduce the burden on budgetary support.

All this is sought to be achieved by tapping the private sector to bring efficiencies in storage and handling operations.

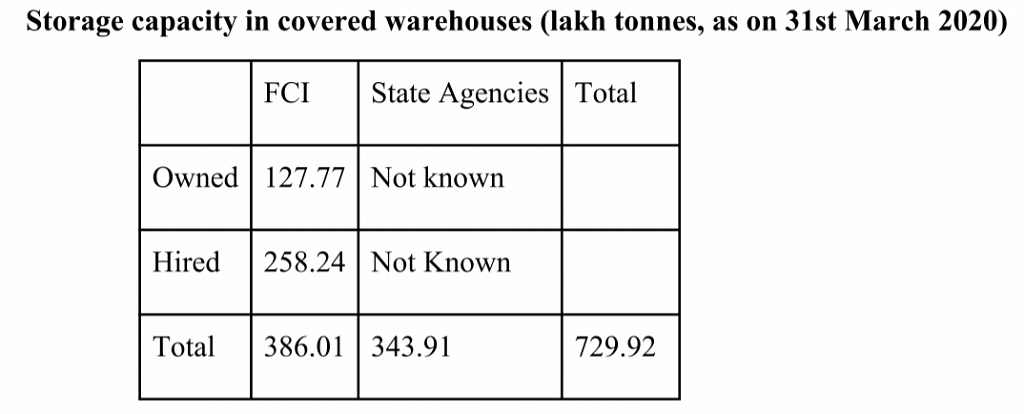

To understand the proposal regarding storage area, let us examine the present storage capacity of food grains procured at MSP for the central pool.

Management and conservation of food grains by FCI

The godowns owned by the Food Corporation of India (FCI) are managed by its own employees. There are two types of freight storage capacity. Some godowns are taken on lease from Central Warehousing Corporations (CWCs) or State Warehousing Corporations (SWCs), which are managed by their respective employees. The godowns taken on lease from private owners are also managed by FCI’s own employees. It should be noted that warehouses store high value food grains and require professional expertise in the preservation and maintenance of quality. FCI, CWC and SWC have a regular and well paid cadre of quality control. Private owners do not even pay their employees.

[Source: Foodgrain Bulletin April 2020]

Out of 258.24 lakh tonnes of capacity hired by FCI, 115.95 lakh tonnes (as on 31 March 2020) was manufactured under the Private Entrepreneurs Guarantee (PEG) scheme launched by the United Progressive Alliance government in 2008. These warehouses are mostly owned. Private owner under ten years guarantee for payment of rent by FCI or state agencies. The entire expenditure on storage, preservation and maintenance is made up of rent payable to the godown owner. Hence, the capacity created under PEG is not available for monetization.

It is certainly possible to offer FCI-owned warehouses to the private sector for preservation and maintenance of stocks. The private sector can do this more economically, as the expenditure on employees may be less than that of FCI.

This is not the first time that warehouses will be offered to private parties for management. In the past, some state governments have tried it and there has been controversy over the quality and quantity of stocks at the time of acquisition for their distribution under the Public Distribution System (PDS).

Therefore, the only storage capacity of FCI that can be monetised is 127.77 lakh tonnes.

How can monetization stop according to NMP

We will try to understand the monetization plan with an example from a warehouse owned by FCI in Mumbai. There are several locations across India – Delhi, Bengaluru, Chennai, etc., which are equally located.

In Borivali, Mumbai, which is an affluent and expensive suburb near the airport, FCI owns Godown With a capacity of about 1.20 lakh tonnes. The godown also has a railway siding, which is situated on a plot of land of about 120 acres. The warehouse was built between 1962 and 1964, and the ownership of the land has been in dispute. It was only last year that decide The land is now the legal owner by the Supreme Court and the FCI.

So, what will this warehouse monetization mean?

Section II of the National Monetization Pipeline states that most warehouses built in the 1980s and 1990s are located in major urban locations. These warehouses can be ‘leveraged’ to enhance the quality of the land as well as increase the capacity of the storage infrastructure. The NMP further states that the private sector may be mandated to undertake the work of redevelopment/renovation of the property.

At another place, the NMP mentions that a silo capacity of 175 lakh tonnes can be developed for storing wheat. In the previous tenders for steel silos, FCI was awarded 30. is guaranteed to pay the storage fee of years.

This means that the Modi government has made up its mind that it will continue to procure wheat at MSP and for this a silo capacity of 175 lakh tonnes will be used. The creation of such additional silo storage capacity also means that direct transfer of food subsidy to beneficiaries is not expected to change.

So, in case of 120 acres of prime land in Borivali, will FCI insist on construction of wheat silos? Or will FCI agree to construct the silo at some other location and leave this land for commercial use? About 16-20 acres of land is required for a 50,000 ton silo with railway siding. FCI already has a silo in Navi Mumbai’s Taloja built and operated by Adani Agri Logistics Ltd. The project became operational in 2007 and the current contract runs through 2027. Wheat is transported in bulk in trains from large silos of 2 lakh tonnes at Moga (Punjab) and Kaithal (Haryana).

The beneficiary of land monetization in Borivali would surely like that the godown is completely shifted so that the entire 120 acres of land can be put to commercial use.

The spirit of the scheme outlined in the NMP is to bring about efficiency and improvement in utilization of existing assets. This would mean that the precious land of Borivali would continue to have storage facilities.

Read also: Now an unusual problem has come in the procurement of wheat – shortage of jute bags

Proper implementation of monetization

FCI’s Borivali godown in Mumbai is an example of valuable assets held by the government and PSUs in many urban locations. I have argued time and again for a ten year perspective plan for the PDS. If physical procurement of wheat and rice and their distribution under the PDS is to continue in 2031 and beyond, the government may decide to place storage capacity for food grains on very expensive land even in the hearts of big cities. An alternative approach could be to close such warehouses on costly land in major cities and set up storage capacity on much cheaper land in rural locations.

Property developers would dream of commercially utilizing such expensive properties located in the middle of urban centres. They are hardly interested in running warehouses or silos at such premium locations and the stated objectives to monetize warehousing infrastructure in urban locations.

Monetization can be a way out of a serious economic crisis resulting from a series of erroneous economic decisions and the resulting slowdown and stagnant revenues of the economy. It would also require a lot of consultation with state governments, whose permission would be necessary for the success of the programme.

It is expected that the revenue from asset monetization will not be used to meet the revenue expenditure of the Modi government or for hypothetical projects of less public use. These assets were mostly created by the previous generation and the next generation is entitled to benefit from the new assets created by their monetization.

The author is a Visiting Fellow at the Indian Council for International Economic Relations (ICRIER) and was the CMD and Union Agriculture Secretary, Food Corporation of India (FCI).

(Edited by Srinjoy Dey)

subscribe our channel youtube And Wire

Why is the news media in crisis and how can you fix it?

India needs free, unbiased, non-hyphenated and questionable journalism even more as it is facing many crises.

But the news media itself is in trouble. There have been brutal layoffs and pay-cuts. The best of journalism are shrinking, yielding to raw prime-time spectacle.

ThePrint has the best young journalists, columnists and editors to work for it. Smart and thinking people like you will have to pay the price for maintaining this quality of journalism. Whether you live in India or abroad, you can Here.