It was a small nook in the corner of the exhibit hall at St. John’s Medical College Hospital. A clothesline bearing a bright red-and-yellow sari, a faded towel and a bright shirt bordered one side of the space, while two filmy curtains constructed out of pastel georgettes saris framed a row of shelves, filled with sundry items, a mirror balanced on the top one. If you stepped past the rag rug splayed across the opening of the alcove, you would enter an innocuous-looking area with a mattress on which an electric iron with an unravelling cable cord, a half-opened sling bag and a closed Kannada novel reposed.

This exhibit, a representation of a sex worker’s home, was one of the most striking ones on display at the recently concluded Mental Health at the Margins, a co-created exhibition developed by the Indian Institute for Human Settlements (IIHS) and the sex worker community in Bengaluru with the guidance and support of Sangama, a Bengaluru-based NGO working on the rights of sex workers and sexual minorities.

“Over one year of workshops, discussions and interviews, several objects emerged that were significant to the participants’ life — a particular sari, medicines, books, beauty products, flowers, and alcohol, among others,” says Sofia Juliet Rajan, journalist-editor from the IIHS Word Lab who has collaborated with Dr Neethi P, Senior Researcher from IIHS Academics and Research and Yashodara Udupa, filmmaker from IIHS Media Lab for this exhibition, the outcome of a year-long study under the Bengaluru chapter of Mindscapes, a mental-health initiative funded by the Wellcome Trust and Unbox Cultural Futures Ltd. “These artefacts were put together as an installation reflecting a home, with the idea that everyone, regardless of what work they do, deserve a safe place to return to at the end of the day.”

A glimpse of their lives

Letters written by sex workers

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Mental Health at the Margins offered a glimpse into the lives of Bengaluru’s sex workers that went far beyond tired cliches. Not only did it dwell on the shame, fear and trauma sex workers regularly encounter, but it offered insights into moments of joy, friendship, and community, suggesting that all these influences shape the mental wellbeing of the community. “We figured that if you are trying to understand someone’s mental space, it is very difficult unless we know what their life has been like,” says Sofia. “We were trying to capture the narratives around the mental wellbeing of the community and their own reflections around the same.”

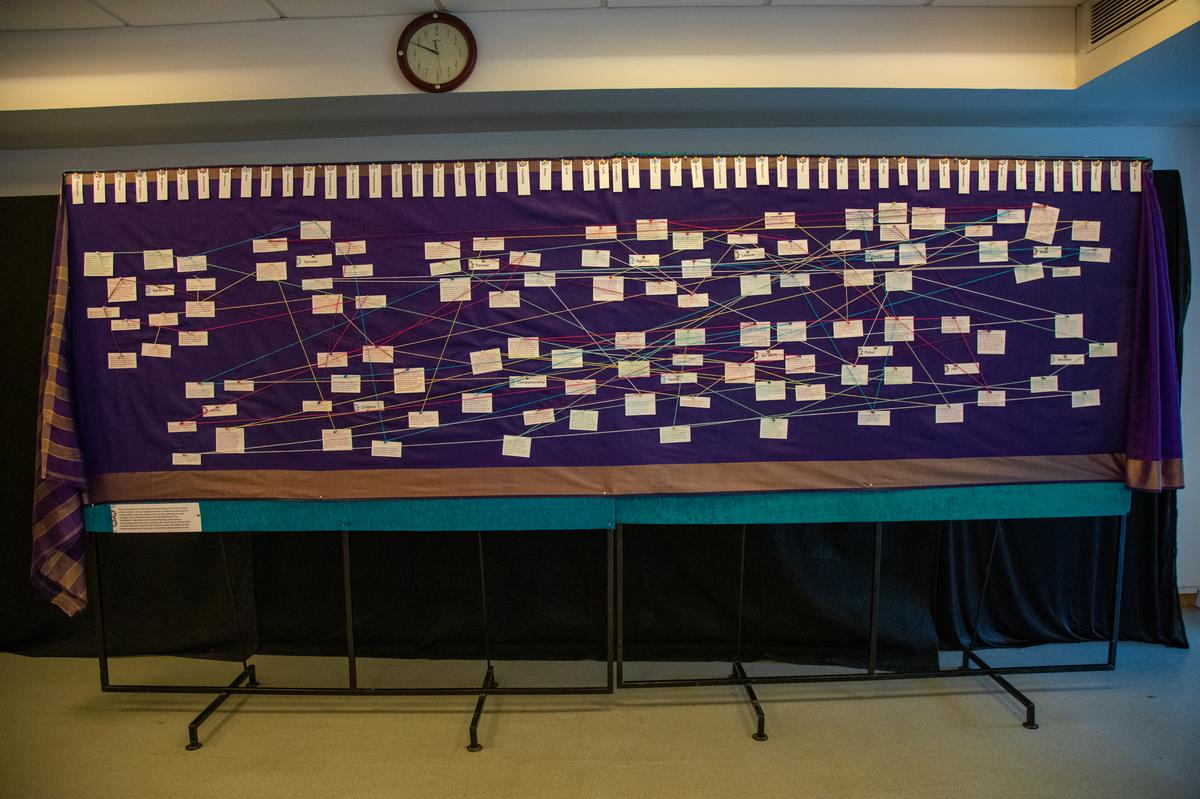

In one corner of the room was a map of Bengaluru on which the sex workers had plotted their memories, emotions, and feelings, reflecting why a particular part of the city was especially significant to them. Beside it was a storyboard that emotionally represented the life journey of these sex workers while a table, in the centre, displayed deeply personal letters written by them. Then, there was an exhibit where everyday pictures taken by the sex workers were displayed, with clippings from various newspapers, a visual representation of how language often cements a prevailing narrative around sex work and the people involved in it.

“We found that the portrayal of these individuals was predominantly viewed through a moralistic lens or reduced to the labels of criminals or victims,” points out Sofia. Prevalent media narratives and public opinion are heavily influenced by this skewed representation, she adds, stating that they had combed through the archives of newspaper articles and headlines from 2000 to the present, looking at coverage of sex workers and sex minorities in Bengaluru. “This lack of empathetic reporting failed to consider the human perspectives and emotions involved in the situation.”

Telling their own stories

Storyboard of emotions

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Yashodara remembers the very first workshop, an ice-breaking session conducted by a mental health professional with the sex workers when they started, back in 2022. “They were asked to recreate Cubbon Park,” she says, recalling how the sex workers went on to play different parts of the park — a tree, a dog, a pair of lovers, even a child. No one, however, played a sex worker, the mental health professional pointed out. “They don’t see themselves represented anywhere, so they don’t represent themselves while telling a story. We had to figure out how to make them see themselves at the centre of the story,” says Yashodara.

Mental Health at the Margins was also about enabling sex workers to gain control of the narrative and tell their own stories, whether they were about abusive families or partners, the threat of HIV/AIDS, and mistreatment at the hands of police or hospital workers or moments of lightness, fun, community and love. The exhibits being displayed, the outcome of these conversations, offered a nuanced take on how mental wellbeing plays out in marginalised communities. “Sex workers, like many other people working in the informal sector, are not just marginalised; they are hyper-marginalised,” points out Neethi, who has been working with street-based sex workers in Bengaluru, for almost a decade now.

This, in turn, means that they deal with “persistent anxiety because of minority stress, including stigma, isolation, prejudice, discrimination and a hostile social environment,” as the exhibition note pointed out, adding that this constant structural and systematic marginalisation is rarely captured by the mainstream policy discourse around mental health. “Many of them feel they are being morally judged when they approach a counsellor,” says Neethi. “It is important to accept them as they are and provide them support.”